Editorial integrity

Our mission is to bring you the most evidence-based, impartial source of nutrition information available. We practice this by ensuring we have a diverse team of researchers who fully read all the relevant scientific papers completely and have no conflicts of interest.

Our goal is to offer neither magical solutions nor pills to help you with your health. Instead, we offer a nuanced and context-appropriate analysis of all the available evidence regarding any nutrition or supplement topic, which gives you the necessary information to make the best decisions for you. We are strongly against any form of sensationalism or emotional manipulation in order to garner more traffic or sales.

Finally, we are very clear that any and all medical issues should be brought to the attention of your attending physician; we are not an alternative to professional medical advice.

We create and maintain structures, workflows, and policies that keep us honest.

Even the most principled people can be swayed. That’s why we are extremely serious about avoiding conflicts of interest: 100% of our revenue comes from subscriptions to our Examine+ membership — we don’t sell supplements, run advertisements, or accept sponsorships. Furthermore, Examine contractually mandates that all staff must avoid any and all connections to supplement, food, or health companies.

We take this policy very seriously, and we have no researchers with any investments, partnerships, contracts, or any other relationship with health-related companies that might bias their research for us. Examine staff are also prohibited from receiving gifts and free samples from health-related companies.

Research quality

We have a rigorous research process, which we are constantly honing.

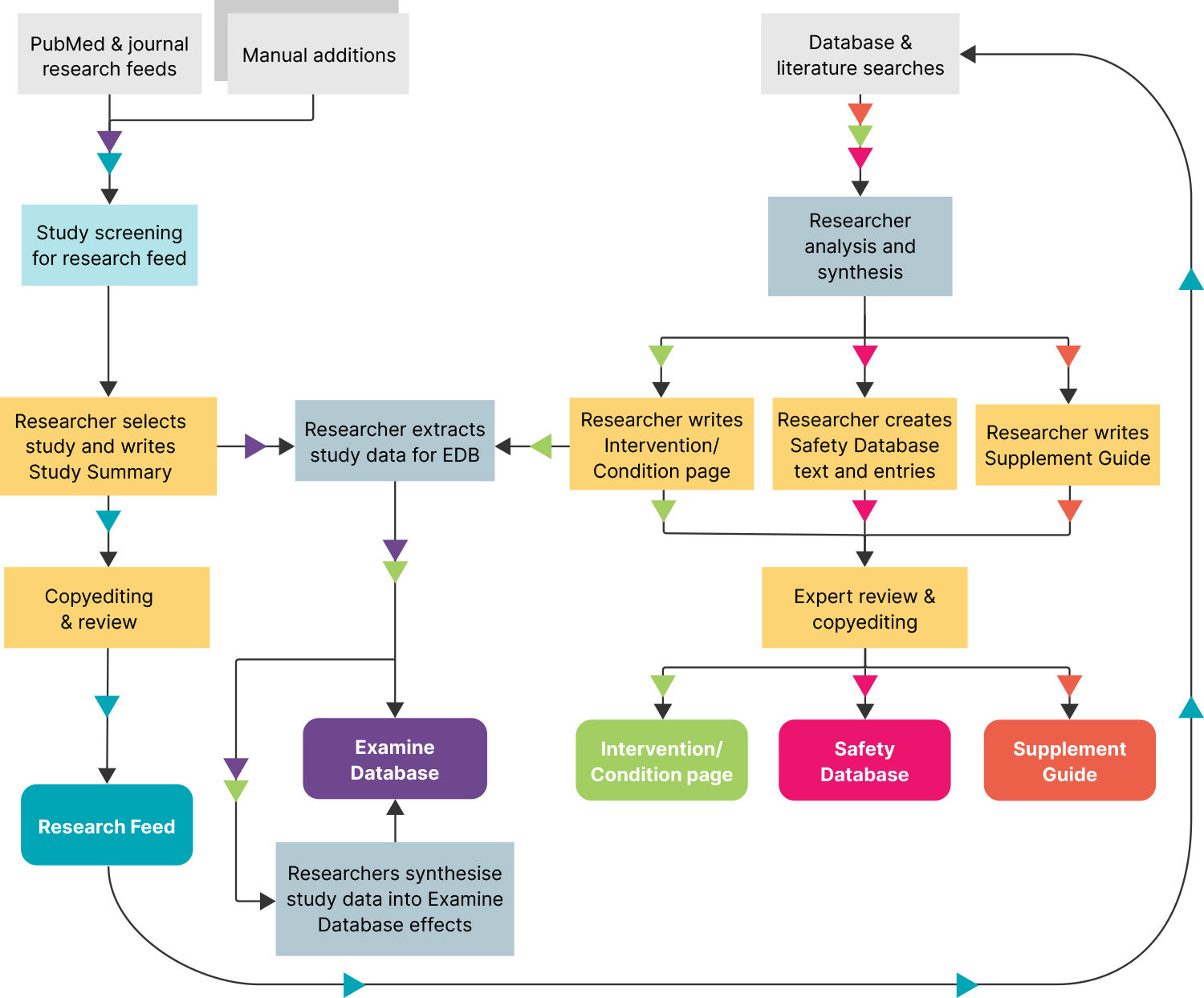

The way we conduct research is slightly different from the way academics might, primarily because we aren’t publishing individual papers — we are constantly updating a library of pages and supplement guides as well as summarizing new studies as they’re published. For that reason, we conduct broad literature reviews several times per week to find any new studies we don’t already cover on our site.

Our literature reviews have an “active” and a “passive” component. The “active” part involves searching a breadth of sources like PubMed and Google Scholar using several hundred search strings. We have a few systematic review specialists on the team who create these search strings, and we also contract with a librarian who has a master’s degree in nutrition to help us fine-tune and update the search strings over time to ensure that we don’t miss any new information. The process is similar to the methods used by federally designated Evidence-based Practice Centers that conduct systematic reviews.

Additionally, we use RSS feeds to monitor the top nutrition journals for new studies as they’re released, in case any slipped through the cracks in the previous step. We also have feeds for several dozen PubMed search strings (created with the assistance of academic librarians) that are designed to find virtually any study that relates to the work we do.

After the studies have been collected, we screen them to make sure they’re relevant to our site. Anything that isn’t relevant is screened out, and the remaining studies are read and analyzed by our research team. We choose the most interesting and relevant studies to summarize in our research feed and extract data from the highest-quality studies to go into our database.

What factors do we consider when reading research?

There’s a ton of subtlety when it comes to evaluating research. Even though most study authors are doing their best work in good faith, almost nothing can be taken at face value alone. Alongside checking the validity of the research methods and theoretical underpinnings of the work, we also dig into the deeper details. Here are some of the questions we ask.

Do any of the study authors have conflicts of interest, ideological axes to grind, or other forces that could shape their motivations?

Bias can creep into research in any number of ways. We always consider funding, and where warranted we may review authors’ publication histories, financial relationships, and even social media profiles, and temper our interpretation of their research accordingly.

How many distinct research groups have contributed to this body of research?

If a single author or research group is responsible for the bulk of the research, bias or fraud in their work can have an outsized impact. Even though meta-analysis methods try to quantify the bias in a body of research, it doesn’t protect well against outright fraud. We prefer to see well-diversified bodies of research and trust their findings more fully.

Are there groups/populations who aren’t yet included in this body of research?

Obviously, selecting a specific population is important in conducting a good study (e.g., if a study investigates the effects of a supplement on the symptoms of menopause, picking menopausal women as participants makes sense). However, it’s quite common for studies to pick a narrower population than might benefit from the findings (e.g., exercise research tends to focus on young men, even though most humans could likely benefit from the findings). If a group or population is underrepresented in a body of research, we do our best to identify which pieces of information can be carried over to them versus which pieces still require more targeted investigation.

How young is this body of research?

Scientific findings tend to become less extreme as increasingly more studies are published on a topic. If a study reports an incredible finding, but it’s the first paper to be published on the topic, it’s probably best to wait to see what other studies say before drawing any strong conclusions.

Dealing with sensationalism

Most online organizations’ core business isn’t education or reporting; it’s driving page views in order to show ads or get sales. As a result, clickbait and sensationalism predominate. The most sensational possible interpretation of a paper’s abstract can win the most page views, and therefore often wins out over thorough, thoughtful reporting.

Examine isn’t in the business of driving page views. Our focus is just the information. We don't need to sensationalize.

We encourage our Examine researchers to continue learning and to share their knowledge.

Nearly all of our researchers come to Examine with some type of prior professional expertise, and they often cover subjects related to it and teach other researchers what they know. However, we also encourage our researchers to cover material that is outside their wheelhouse. In fact, sometimes they’re asked to research topics that don’t match up with their personal diet and supplement regimens. For example, if a researcher eats a ketogenic diet, they have to be equally adept at analyzing vegan diet studies without exhibiting bias. And if a researcher eats a vegan diet, they have to be equally adept at analyzing ketogenic diet studies. Not only does intentionally branching out help expand our team’s knowledge, but it also helps everyone on the team keep a “beginner’s mind”, which reminds them that there’s always more to learn and that no one person’s experience is the universal truth.

Team members are also encouraged to host internal seminars about their topic of expertise. These have included deep dives into statistics, the philosophical underpinnings of research methods, and the stylistic subtleties of science writing.

We review our work extensively.

We have a team of skilled copyeditors, led by a specialized medical editor, to make sure that our writing clearly communicates the key concepts without being unintentionally misleading. Next, an internal reviewer (and sometimes an external reviewer, too) goes line by line and comments on an analysis that may not be interpreted correctly or topics that need more explanation.

The end result is that everything is triple-checked on the website, which ensures that we minimize bias as much as humanly possible. We hire researchers and reviewers from a wide variety of backgrounds (dietitians, PhD researchers, pharmacists, medical doctors, etc.), which makes it a quick process to root out any bias that can affect the veracity of our writing.

We stay tuned in to the research, even when we are finished writing.

Science is an ongoing process — our understanding of topics constantly evolves, and so does the material on our site. We constantly update our work as new research comes out as well as when papers are retracted. We’ve created a tool that automatically checks the Retraction Database against our site to see whether any of our work cites retracted material, so that we can make updates and corrections accordingly.

We’re open to corrections.

Examine is committed to making corrections and clarifications, should any issue come to light. We take prompt action to review any concerns brought to us by our readers, and if warranted, immediately update any content on the website. This includes new information that was not available at the time of publication and any other necessary updates to an article.

If you believe you’ve found anything incorrect on our website, please contact us. Our goal is to be the single most accurate and up-to-date source of nutrition information available.

Why should I use Examine instead of an AI tool like ChatGPT or DeepSeek?

Large language models (LLMs) are tremendously powerful tools, and when they are applied correctly, they can be very helpful for conducting research. There are some obvious shortcomings (such as hallucinations or “stuff that the LLM makes up”), but let’s also look at some more nuanced ways in which LLMs fall short of expert humans (like us).

LLMs suffer from hallucinations.

All of the current large language models sometimes generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information, a problem known as “hallucination”. When an AI-generated search summary claims that hippos can perform complex medical procedures (true story), that’s a hallucination that anyone over the age of 5 can spot. But hallucinations are very hard to spot when asking AI anything that you don’t already know the answer to. So trying to learn new things from AI tools carries a risk of learning plausible, but factually incorrect, information. In contrast, every piece of information on Examine’s website has been researched, summarized, and vetted by multiple human experts. Our experts can make mistakes — that’s why we have multiple pairs of eyes on everything we post — but we’ll never make stuff up.

LLMs take studies at face value.

Although research methods aim to remove human factors as much as possible, it’s not a perfect process. Research is often published with errors in the data reporting or methods and, occasionally, outright fraudulent findings. Although an LLM can summarize the findings of a paper, they can’t reliably decide whether the right statistical tests were used, whether a particular biomarker level is impossibly high, or if the scientist who published the work is known for having a strong bias or dubious practices. Without careful prompting, they also won’t flag potential conflicts of interest — such as when a supplement study is conducted and funded by the company that makes it.

When summarizing research, LLMs can’t weight studies based on their merits.

Studies vary in many ways, including size, quality, and methods. Although some studies are obviously excellent and some studies are clearly terrible, most studies lie somewhere in the middle. An important part of making sense of a body of research is figuring out how much a given study should change your conclusions based on (a) what you already know and (b) the size, strength, and quality of findings presented in the study you’re reading. Our researchers have spent years (often decades) honing their ability to weigh these subtle factors, but LLMs aren’t yet able to do so.

LLMs are only as trustworthy as their training data.

The most well-known and popular LLMs are trained on vast amounts of data from all over the internet. As you may know, the majority of nutrition reporting on the internet is subject to considerable bias, and as a result, the output from LLMs frequently reflects this bias. Similarly, without careful prompting, LLMs can’t tell what types of information are useful to you, and may, for example, return results based on in vitro studies or animal studies.

LLMs can’t (or shouldn’t) access paywalled content.

Generally speaking, LLMs can’t access (and won’t base their results on) paywalled materials, like the full text of a research paper. Many LLMs will draw conclusions from free abstracts, which don’t always reflect the paper perfectly. Examine’s experienced human researchers always read the paper’s full text. We recognize when a study abstract misrepresents the study’s conclusions, and our research summaries reflect that.

LLMs are easily influenced by spin.

Because of publishing pressures, researchers may be incentivized to present their findings with a positive spin (e.g., saying a finding “trends toward significance”, rather than saying “isn’t significant”). LLMs tend to take this spin at face value and will consequently have a bias toward reporting meaningful effects, even when none are present.

LLMs struggle with niche topics.

In order for an LLM to effectively cover a topic, there needs to be enough written, accessible, and relevant source material. Many of the topics we cover have relatively few studies, so discussing these topics often requires accurately (and responsibly) filling in the gaps from domain knowledge or conceptually similar findings — a task that expert humans still excel in.

How is ExamineAI different?

ExamineAI is designed strictly as a way to help you quickly and easily navigate the vast ocean of information available on Examine. Unlike ChatGPT or DeepSeek, ExamineAI will always base its answers on evidence-based Examine materials, each piece of which has been triple-checked by our internal and external reviewers. ExamineAI will not retrieve information external to Examine. That said, LLMs can make mistakes, so please refer to the linked references included with each response to ensure accuracy. Learn more about ExamineAI here.

What are the different sections of the website about?

Examine.com has several sections that present research in different, but complementary, ways designed to help our users navigate the body of research.

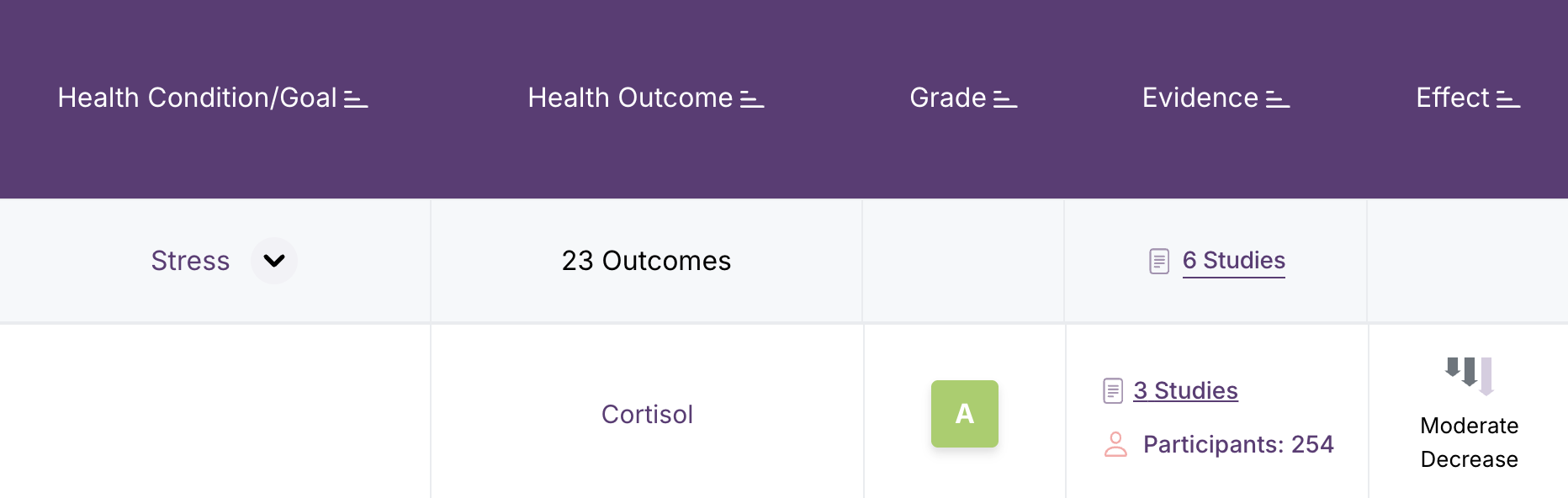

Examine Database

The Examine Database is where we collect data exclusively from randomized controlled trials in humans or from meta-analyses of these trials. It displays the overall magnitude (size) and direction (bigger or smaller) of an effect on a specific health outcome and a grade that is a composite evaluation of consistency between studies, the total number of studies we’ve considered for a given outcome, and the magnitude of the effects reported in those studies. Interventions that are indexed in the Examine Database are assigned a letter grade from A to F, with A indicating the most effective and F denoting those that are unsafe for that specific outcome. Examine grades are automatically calculated from the following 3 main inputs:

- Magnitude of effect

- Consistency of effect across studies

- Number of studies

How do effect magnitudes work?

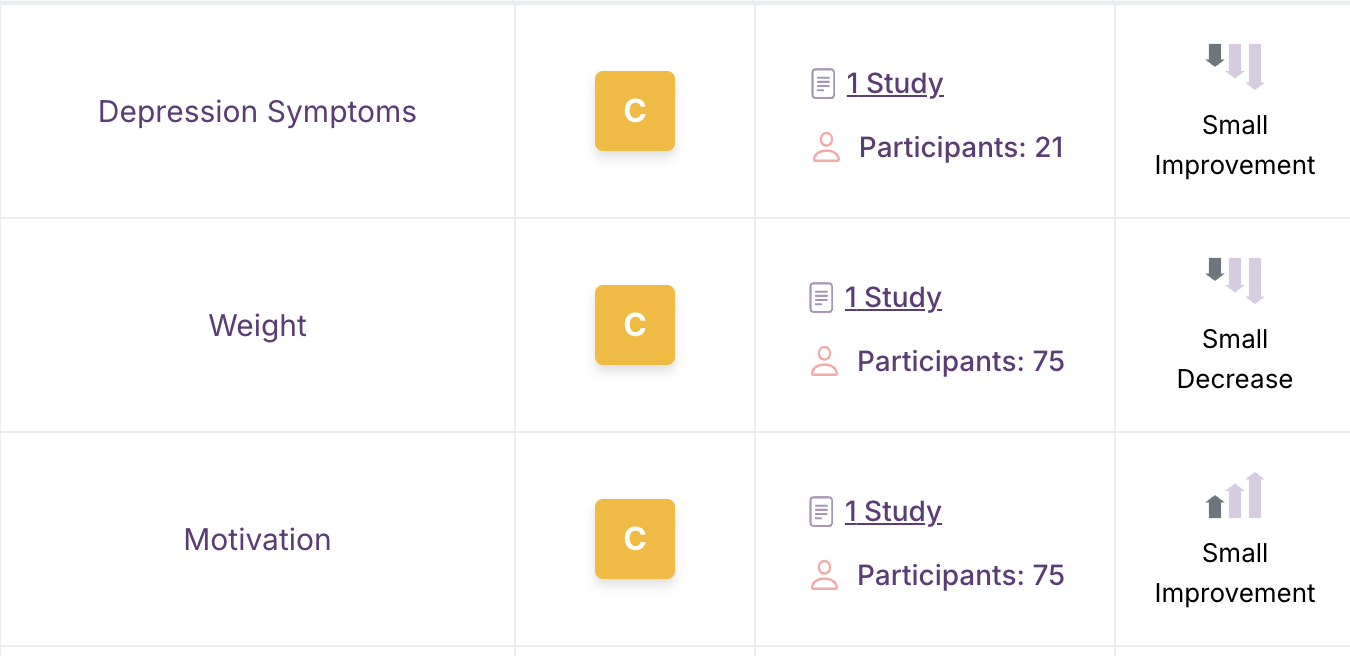

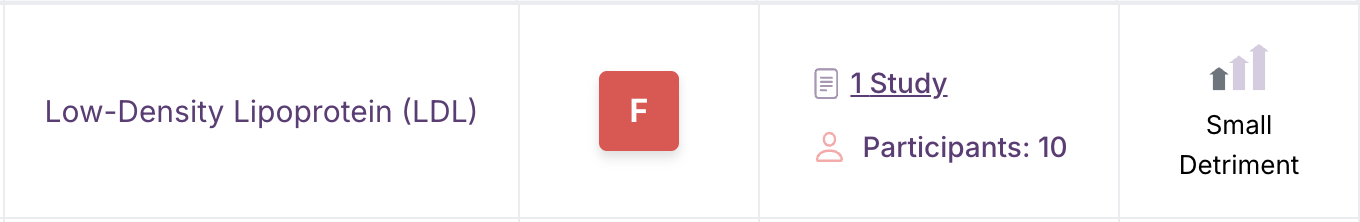

Effect magnitudes (the arrows in the Effect column) are entered by hand by our expert research team. Examine researchers look at the body of evidence rather than single trials. They assess the magnitude of effect for any intervention that is studied for a specific outcome and take into account both the absolute magnitude and the clinical significance to determine the overall direction (increase, decrease, mixed, or none) and size (small, medium, large) of the effect.

Upward-pointing arrows mean that the outcome is increased. Downward-pointing arrows indicate a decrease in the outcome. A dash indicates no effect. Arrows that point up and down indicate a mixed effect that depends on the specific context of the study.

There’s an interpretation below the effect magnitudes to indicate beneficial vs. harmful effects. “Improvement” indicates a beneficial effect, “detriment” means a harmful effect, and “decrease/increase” indicates that whether there is a benefit or harm depends on the specific context (like testosterone, which is “good” when it goes down in a woman with polycystic ovary syndrome but “bad” if it decreases in an older man who is doing strength training).

For example, depression symptoms going down is almost always good. So if an intervention decreases depression symptoms, the Examine Database labels its downward-pointing arrows as an “improvement". In contrast, a decrease in weight may be good in a person with a weight loss goal, but under other circumstances may be undesirable; therefore, that outcome’s downward-pointing arrows are simply labeled “decrease”.

What do the letter grades mean?

- A: Multiple, mostly consistent studies suggest at least a moderate effect.

- B–C: Fewer studies suggest a possible effect, there’s some inconsistency in the data, or the effect is small.

- D: Either there’s very little research on the topic, the studies are highly inconsistent, the effect is null or very small, or a combination of these issues.

- F: The evidence indicates that the intervention may make that specific outcome worse for the specific condition which that grade applies to.

You may notice that the grades vary a little between different pages on our site. That’s because we use different evidence depending on the population from each study. For example, something that helps lower inflammation in people with polycystic ovary syndrome may not help as much in people with cardiovascular disease. So the specific page you should look at depends on your goal:

- If you care about all the effects of the intervention, check out the Examine Database on the specific intervention’s page.

- If you care about what’s best to take for a specific condition (like type 2 diabetes) or goal (e.g., aerobic exercise performance), visit our Conditions and Goals pages.

- If you care most about improving a particular outcome (like HbA1c or VO2 max), then you can peruse the Examine Database on that outcome’s page.

We’ve also calculated grades for how interventions affect some conditions/goals as a whole. You’ll see these on intervention pages in the Examine Database. These grades reflect the effects of the intervention on the most important outcomes for that condition or goal.

For example, for the condition of migraine headache, the outcomes migraine symptoms, migraine severity and migraine duration are considered primary because these combined outcomes are essential to migraines: If they all decreased a lot, you’d be pretty likely to say that your migraine headaches improved drastically. We use the data for these primary outcomes to calculate a condition grade for interventions that affect these outcomes. In contrast, outcomes like nausea are relevant to many migraineurs but not primary; we wouldn’t say that an intervention that only affects nausea is effective for migraine. Thus, while nonprimary outcomes may be of interest, they are not used in calculating condition grades for the condition of migraine.

If we don’t have data for those primary outcomes, we won’t calculate a condition/goal grade, but you can still see the individual outcome grades. For example, if the only results we have for lavender in people with ischemic heart disease are lavender’s effect on sleep quality, we won’t give lavender a condition grade for heart disease. Some conditions/goals intentionally don’t have grades because they’re broad, like metabolic health, or because the most important outcomes aren’t best treated with the types of interventions we cover, like thyroid cancer.

Frequently Asked Questions

As the name suggests, our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) are designed to answer all the questions that might come to mind when learning about a topic. Every one of our pages has a set of standard questions as well any number of topic-specific questions. For example, our Vitamin D page includes the following standard questions:

- What is vitamin D?

- What are vitamin D’s main benefits?

- What are vitamin D’s main drawbacks?

- How does vitamin D work?

It also has the following questions that are more specific to vitamin D:

- How much sun do I need for vitamin D production?

- Does sunscreen decrease vitamin D?

- What are some of the factors that can increase the risk of having a vitamin D deficiency?

When we are writing FAQs, we primarily draw from systematic reviews and clinical guidelines if these are available, or individual randomized controlled trials if not, but we also draw from observational (and occasionally animal) studies and biological mechanisms to expand our audience’s understanding of the topic, when it’s relevant. We always clarify what type of research is used to support a claim and how definitive we can be based on the type and quality of the study.

Safety Information

The Safety Information provides a focused look at safety concerns that are relevant to a particular intervention. Within the Safety Information, you can find information regarding adverse effects, interactions with medications, general or population-specific precautions, safety during pregnancy and lactation, and concerns related to supplement quality such as contamination and adulteration. Ultimately, the Safety Information helps you answer the question “Is this safe for me (or my patient) to take?”

Our team of healthcare professionals — including pharmacists, nurses, and medical doctors — develop the Safety Information by completing a thorough review of safety concerns identified in clinical trials, case reports, observational studies, government reports, and occasionally animal and in vitro research. We use this evidence to communicate the certainty (or uncertainty) of these safety concerns, their likelihood of occurring, and what populations might need to take particular caution.

What is included or excluded in the Interactions section?

✅ We include the following:

- Interactions observed in in vitro studies, animal studies, case reports, and clinical trials.

- Interactions involving medications, supplements, alcohol, cannabis, or tobacco.

- Interactions with the following cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes: CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2A6, CYP2E1, CYP2J2, CYP4F2.

❌ We don’t include the following:

- Interactions with CYP enzymes NOT on the list above

- In vitro CYP induction studies that are less than 48 hours in duration. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines recommend 48 to 72 hours of incubation to allow for complete induction; if the time is shorter, the reasoning should be clearly explained.

- Mechanistic studies. These are exploratory in vitro or animal studies that broadly explore the potential effects of an ingredient or a supplement. The goal of these studies is to find therapeutic uses for supplements that would warrant further clinical testing.

- In silico studies. These are computer-based investigations that can be used to support or refute signals found by in vitro/in vivo studies, but not as stand-alone evidence to support interaction potential.

How do we determine the Level of Evidence and Level of Severity for interactions?

When looking at the interactions, you’ll notice that each interaction is assigned a Level of Severity and Level of Evidence. The goal is to communicate how strong the evidence that supports the interaction is and how severe the outcomes might be.

Based on the available research, interactions can be classified as probable when they are supported by strong clinical evidence (e.g., multiple clinical trials and case reports), possible when they are based on a single clinical trial or a case report, or theoretical when only observed in in vitro or animal studies.

The severity of an interaction can be classified as severe when the interaction is life-threatening or causes permanent harm, moderate when it worsens a condition and requires monitoring or a therapy adjustment, minor when it’s unlikely to cause harm and does not require any change in treatment, or unknown if there is insufficient evidence to predict the interaction’s clinical impact.

Are the interactions and/or side effects dose-specific?

We only include information on the dosage at which an interaction or side effect occurs if the dosage at which the interaction/side effect was observed was abnormal (e.g., outside of the commonly used range), or the interaction/side effect is dose-dependent.

What is included or excluded in the side effects section?

✅ We include side effects observed in humans in case reports or clinical trials. In case reports, side effects should ideally be supported by causality testing (e.g., dechallenge/rechallenge – i.e., the effect disappeared on stopping the drug and reappeared on restarting – or allergy testing) or other factors (e.g., temporal relationship, dose-response effect). In controlled studies, a side effect should ideally occur more frequently in the intervention group than in the placebo group (and reach statistical significance, if a statistical analysis was done).

❌ We don’t include side effects that have only been observed in animal models, but not in humans.

Research Feed

Although most of our site talks about the overall research on a subject, our Research Feed analyzes and summarizes individual studies not long after they’re published. In each of our summaries, we discuss the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the study in question, and we analyze the study’s methods and possible conflicts of interest. We also release 10 Editor’s Picks each month, which have all the qualities of a regular summary plus extra details and a “big picture” section, where we discuss how this particular study fits into the body of research on a subject overall.

Supplement Guides

Developed from the entire body of Examine’s evidence-based data, the Examine Supplement Guides are designed to help our readers understand how different supplements compare to one another and which are most likely to be helpful for a given health condition or goal. It’s relatively rare for different supplements to be tested head to head, so our guides take many factors into account, from the number of studies and their quality to how easy and safe they are to use. For each of our guides, we provide whatever background information is required to understand the subject at hand and rate supplements by how advisable it is to take them. The supplements are rated as follows:

- Combinations of supplements are our top picks — the most proven, safe, and effective supplements, chosen to be complementary and to avoid redundancy.

- Primary supplements have the best safety/efficacy profile. When used responsibly, they are the supplements that are most likely to help and not cause side effects.

- Secondary supplements are less effective, less safe, or less proven, but still potentially beneficial and worth taking if primary supplements aren't sufficient or feasible to use.

- Promising supplements have less evidence for their effects. They could work or be a waste of money, and it’s too early to say which.

- Unproven supplements are backed by tradition or by animal, epidemiological, biological, or anecdotal evidence, but not yet by convincing human trials.

- Inadvisable supplements are either potentially dangerous or simply ineffective, marketing claims notwithstanding.