Study under review: Cannabis and creativity: highly potent cannabis impairs divergent thinking in regular cannabis users.

Steve Jobs once said that “marijuana and hashish … make me relaxed and creative.” And many people agree with his assessment. One study found that over 50% of users report enhanced creativity when using marijuana. But Steve Jobs was wrong about things before (the Apple Lisa, anybody?). Could he have been wrong about marijuana enhancing creativity as well?

Researchers know enough about the brain to take a decent stab at predicting how marijuana may affect creativity. The story starts with the neurotransmitter dopamine and its influence on two cognitive processes first fleshed out in the 1960s, a decade of great creativity!

While creativity is a hard thing to measure objectively, some components of it are being teased out. Specifically, two cognitive processes are thought to play a strong role in creativity. They are called convergent and divergent thinking. Divergent thinking is best described as the skill behind brainstorming — it’s being able to explore options through loose associations to generate novel ideas. Convergent thinking works in the opposite direction: It takes a bunch of loosely-organized ideas and finds a common thread between them.

There is a common thread winding its way through these thought processes and dopamine. Dopamine is often thought of as the “reward neurotransmitter” (although this is a major overgeneralization because dopamine has multiple functions). However, it also seems to have a role in the neuroscience of creativity. Specifically, one study in light marijuana users found that dopamine has a negative linear correlation with convergent thinking, whereas it shows an “inverted U” shape correlation with at least one aspect of divergent thinking, where too much or too little harms it, but a middle amount is just right.

The main psychoactive ingredient of marijuana, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is known to stimulate release of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the striatum, a part of the brain involved in creative activities such as writing (and also addiction). Chronic marijuana use, however, may lead to depressed dopamine activity.

On the basis of marijuana’s effects on dopamine and creativity in light users, the authors of the current study formulated a hypothesis on marijuana’s effects on divergent and convergent thinking in heavy users. Since long-term cannabis users would have depressed dopamine activity, their divergent thinking before inhalation would be on the left hand side of the “inverted U” curve, but inhaling marijuana may push them temporarily to the right on that curve, improving divergent thinking. Convergent thinking, however, is negatively correlated with dopamine activity, so inhaling marijuana should hamper this aspect of creative thinking in anyone, whether they regularly use marijuana or not. These relationships are summarized in Figure 1.

The goal of the current study was to put this hypothesis to the test.

Two aspects of creativity are related to dopamine activity in the brain. Divergent thinking, the skill behind brainstorming new ideas, may get worse with very low or very high dopamine activity, and is best in the middle range. Convergent thinking, the skill behind unifying ideas into a coherent whole, worsens as dopamine activity increases. Since long-term marijuana users have depressed dopamine function, use of marijuana in this population could improve divergent thinking while worsening convergent thinking. This hypothesis was put to the test in the current study.

Who and what was studied?

A total of 54 healthy Dutch people (6 women and 48 men) in their early 20s who regularly used marijuana were included in this study. “Regular use” was defined as consuming marijuana at least four times per week for the past two years. “Healthy” here meant that the participants did not have significant mental or physical disorders, did not abuse alcohol, were not on any psychotropic medications, and did not use any other drugs recreationally. People who smoked cigarettes were included in the study.

The participants were randomized to inhale vaporized marijuana that contained one of three levels of THC. Attached to the vaporizer (a Volcano-brand vaporizer, depicted in Figure 2) was a large balloon that filled with the vapor. The participants were asked to inhale deeply the content of the balloon and hold their breath for ten seconds before exhaling. It was a pretty big balloon, so it took several inhalations to completely consume its contents.

The total amount of THC delivered to each participant in the three groups was 22 mg (high dose), 5.5 mg (medium dose), or almost 0 mg (placebo). Acknowledging that not all the THC in the plant is vaporized, and that not all of the inhaled THC is absorbed through the lungs, the researchers estimated that the actual doses absorbed were 8 mg, 2 mg, and 0 mg, respectively. The participants and experimenters were blinded to what dose of THC was being delivered.

The participants were asked to report their subjective feelings 6 minutes after completely consuming the marijuana. They were also given two 10-minute tests: the first, 35 minutes after consuming the marijuana; the second, 60 minutes after consuming the marijuana. But … how can you measure creativity? Well, psychologists, being a somewhat creative bunch themselves, have come up with a few tests, two of which were used here.

The Alternate Uses Test (AUT) measures divergent thinking. People taking the AUT must generate as many uses for a common household item as possible within a given span of time. For instance, a pen can write, hold a door open, be used as a bookmark, be melted and molded into a shape, etc. The answers were then rated by two independent reviewers blinded to the treatment condition, according to four different criteria: fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration. The scores highly correlated with each other, which suggests that the tests were rated reliably.

The Remote Associates Task (RAT) measures convergent thinking. Participants are given three words and must find a fourth word that links them. One example is “back, go, light.” The fourth word for this set is “stop.” Since the RAT has “objective” answers, it is easier to come up with a final score for it than for the AUT: You just count the number of right answers.

The tests were administered in a random order to each participant to make sure the order of administration didn’t affect the results. Also, after each creativity test, the experimenters again asked the participants to rate their subjective feelings.

To test the effect of cannabis on creativity, this study recruited 59 young, healthy people who frequently used cannabis. The participants were randomized to inhale marijuana that contained either a high dose of THC, a medium dose of THC, or almost no THC. After consuming the marijuana, they took two tests of creativity: the Remote Associates Task (RAT), which measures convergent thinking, and the Alternate Uses Test (AUT), which measures divergent thinking. Their subjective feelings were also measured throughout the experiment.

What were the findings?

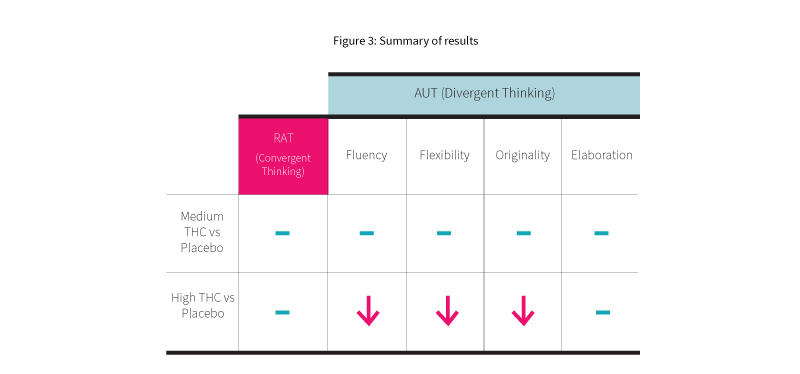

The study’s findings are summarized in Figure 3. The three treatment groups did not differ in convergent thinking as measured by the RAT, indicating that the THC content of marijuana did not affect remote associations in this population.

Also, there was no difference between the performances of the placebo group and the medium-dose group on any of the four subscores of the AUT, indicating no effect on divergent thinking at this dose of THC. However, the high-dose group performed significantly worse on three of the four AUT subscores, with no difference between the three doses for the elaboration subcategory.

Before inhaling marijuana, the participants in this study had performed similarly to people not under the influence of any substances, on both the AUT and RAT.

Participants were asked to assess their “subjective feelings” by grading three kinds of effects: “feeling high”, “good drug effects”, and “bad drug effects”. The medium- and high-dose THC groups gave similar scores to both “feeling high” and “good drug effects” (the placebo group gave lower scores). The placebo and medium-dose THC groups gave similar scores to “bad drug effects” (the high-dose THC group gave a higher score). THC level did not affect measures of mood, and mood did not change significantly over time.

Convergent thinking as measured by the RAT was not affected by THC at any dose. Divergent creative thinking was unaffected at medium doses of THC, and made worse in three of four subcategories of the AUT at high doses, with no effect on the fourth category of elaboration.

What does the study really tell us?

The study provides some evidence against the view that marijuana enhances creativity. Instead, it seemed to have either no effect or a negative effect. But, as usual, there are a lot of caveats to this statement.

First, the measures of creativity used in this test were all based on word associations on the written page. It is not immediately clear if this relates to creativity in other domains, such as the visual arts, dance, music, or the spoken word. There is some evidence along with varying hypotheses that address how related different types of creativity are, but results are quite mixed, and studies use varying methodologies.

Second, the study participants had all used marijuana fairly heavily for at least two years. Even if we can trust the results (and one study never proves anything), they only apply to people who have used marijuana similarly. Third, different marijuana strains can have wildly different effects. Fourth, those effects can also vary between different people.

Perhaps the authors’ starting hypothesis, as presented in the introduction, could shed some light here … if the results from their study supported it. But why don’t they? Maybe because the authors based their hypothesis on just one previous study, which used eye-blinking rates as a proxy for dopamine activity – a less-than-entirely reliable indicator.

The authors of the study mention the possible unreliability of eye blink rates as a measure of dopamine activity. They also present a few other possible reasons why their hypothesis didn’t seem to hold in the study. One possibility is that the high-dose group received too high a dose, pushing them to the far right of the inverted U-shaped curve. A more fine-grained dosing study in the future could shed some light on this possibility. Alternatively, the authors noted that the high-dose group experienced more negative effects than the other two groups. This led them to suggest that maybe the participants had to spend their cognitive resources dealing with the bad feelings rather than with the task at hand, which fits with the “ego depletion” model of cognitive control.

As for why the placebo and low-dose groups performed equally in the AUT, the authors suggest several possibilities. One is that the dose was too low, since the participants were tolerant to THC and some studies have shown that higher doses are needed for the same effect in this population. Alternatively, the placebo may have contained enough THC (or other active ingredients) to exert an effect. Finally, perhaps the placebo effect was strong in the placebo group, since what they inhaled was identical in smell and taste to marijuana with a higher THC content. This may have led to increased dopamine output simply based on expectation, which is an effect that has been noted in other studies.

The authors did not provide as many possible explanations as to why convergent thinking didn’t differ between any of the treatment groups. The main hypothesis they put forward is that they used a truncated, 14-question version of the RAT, which may not have been sensitive enough to measure differences accurately. Many possible factors weren’t discussed, such as the impacts of cannabinoids from marijuana on non-dopamine aspects of brain function, some of which may theoretically impact creativity.

The generalizability of this study is limited, both because it was done exclusively in people who used marijuana heavily and because it only measured two aspects of creativity, both related to words on a written page. In addition, this study generated a lot of hypotheses as to why the predictions of the authors didn’t pan out, many of which could be tested through further research.

The big picture

The current study somewhat clashes with a larger body of research on marijuana’s and THC’s effects on convergent and divergent thinking. The effects on divergent thinking tends to have more evidence surrounding it.

Early research using THC cigarettes found that 3 mg of THC improved divergent thinking, whereas 6 mg worsened it. Later research using oral THC noted increased verbal fluency in doses up to 15 mg. Long-term users of cannabis were tested in another study that found that smoking marijuana improved divergent thinking, but only in people who assessed themselves as not very creative in the first place. Yet another study found that smoking marijuana improved aspects of divergent thinking only in long-term users, but not in people without a long history of exposure to cannabis. While all the previous studies found an improvement in divergent thinking, at least in some populations, one study came up empty-handed.

Studies on marijuana’s effect on convergent thinking are fewer and far between, and both were mentioned above. One of those two studies found convergent thinking to be impaired by joints containing 3 or 6 mg of THC, compared to a control. Another, later study used the RAT and found that marijuana containing 10% THC may harm convergent thinking in people who rated themselves to be fairly creative.

While the conclusions that can be drawn from the body of research are not crystal-clear, it seems that the current study goes against what little evidence there is concerning marijuana’s effects on creativity, at least to some degree. Fortunately, contradictory and confusing research can serve as grist for the mill of scientists’ creativity in the future as they search for solutions.

Previous research done on marijuana’s and THC’s effects on convergent and divergent thinking tends to indicate that acute marijuana use can improve divergent thinking and harm convergent thinking. However, the evidence to date is limited and mixed.

Frequently asked questions

Q. How potent was the marijuana used in this study compared to that of average marijuana?

Most marijuana is 5–10% THC, although THC content has been rising sharply in recent years, sometimes hitting the 30% mark. For comparison, the highest THC dose in this study was the equivalent of around 9% THC. However, the participants in this group had to inhale a large balloon full of the vapor, which required several hits.

Q. This study was done in long-term users of marijuana. How would marijuana affect the creativity of people who don’t use it frequently?

By the reasoning laid out in the introduction, marijuana use should make both divergent and convergent thinking worse. Recall that convergent thinking is inversely correlated with dopamine activity and divergent thinking has an upside-down U-shaped correlation with respect to dopamine activity. This implies that any increase in dopamine activity will worsen convergent thinking, just like in people who use marijuana heavily over the long-term. However, since people who don’t use marijuana frequently will lie in the middle of the inverted “U” curve for divergent thinking, occasional marijuana use could push them to the far right of the curve, worsening their divergent thinking as well. This is different from the prediction the authors made for chronic cannabis users.

That’s the theory, anyway. As the study reveals, it didn’t quite pan out as expected.

Q. So the authors’ hypothesis was that marijuana’s effect on creativity is mediated by dopamine. Does this mean that other drugs that affect dopamine could affect creative thinking?

Assuming the authors’ hypothesis is correct (which isn’t a great assumption, given the results of this study), this would indeed be the case. In fact, it’s somewhat odd that the authors of the current study didn’t take their hypothesis to its logical conclusion and mention other drugs in their discussion section.

There aren’t a whole lot of solid studies on other drugs’ effects on creativity. One study on Adderall, which affects dopamine levels, found no effect on divergent thinking, and a positive effect on convergent thinking, but only in those who scored lower in convergent thinking to begin with; those with higher convergent thinking ability to start out with were either unaffected or impaired.

Q. Are there also supplements that could affect creative thinking?

Remember that dopamine activity is related to creative thinking. Dopamine is synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine. So, in theory, it’s possible that tyrosine supplementation could affect creativity. One group recently put this hypothesis to the test and indeed found that tyrosine improved convergent, but not divergent, thinking. While one study doesn’t prove anything, this is an interesting result. Hopefully, more research will be done in this area.

Q. Do all strands of marijuana have the same effects? Might other strains boost creativity?

Different strains of marijuana differ in their molecular composition, most notably the overall amount of cannabinoids and their relative ratios. Since some effects of marijuana are linked to Delta-9-THC alone, others are attributed to cannabidiol, and others are not even traced back to specific cannabinoids (or interplay between them), it is very possible that different strains can significantly differ in effects.

Ultimately, however, most scientific studies focus on the cannabidiol and THC content unless they have a reason to focus on other cannabinoids. While it can give insight as to which plays a more significant role, the question of whether or not one strain is “better” than another for a given purpose (such as creative thinking) requires more direct testing or, on the consumer side, some experimentation. Trials such as the current one provide some basis for future research on different variables (different amounts, strains, populations, etc.).

What should I know?

This study found that acute marijuana use in heavy users had no effect on the aspect of creativity called convergent thinking, which is the ability to unify disparate themes into a common thread. It also found that marijuana that contains high doses of THC may impair divergent thinking, which is the ability to brainstorm and come up with unique, loosely connected ideas. Marijuana containing lower doses of THC had no effect on divergent thinking. These results were somewhat unexpected based on past research.

Now that we’ve covered marijuana’s effect on your creativity, let’s dig into how it can impact your appetite. Click here to read about the science behind munchies.

Or you can also see our incredibly detailed page on marijuana itself.