Why has intermittent fasting (IF) become so popular in the past few years?

One of the main reasons is simplicity. There are a million and one diets that involve specific foods or nutrients, but IF skirts all those details. Let’s see what the main types of IF are, and what the evidence shows about weight loss and other health effects.

IF variants

Also known as time-restricted feeding,[1] IF alternates periods of normal food intake with extended periods (usually 16–48 hours) of low-to-no food intake. This approach lends itself to different variants, including those:

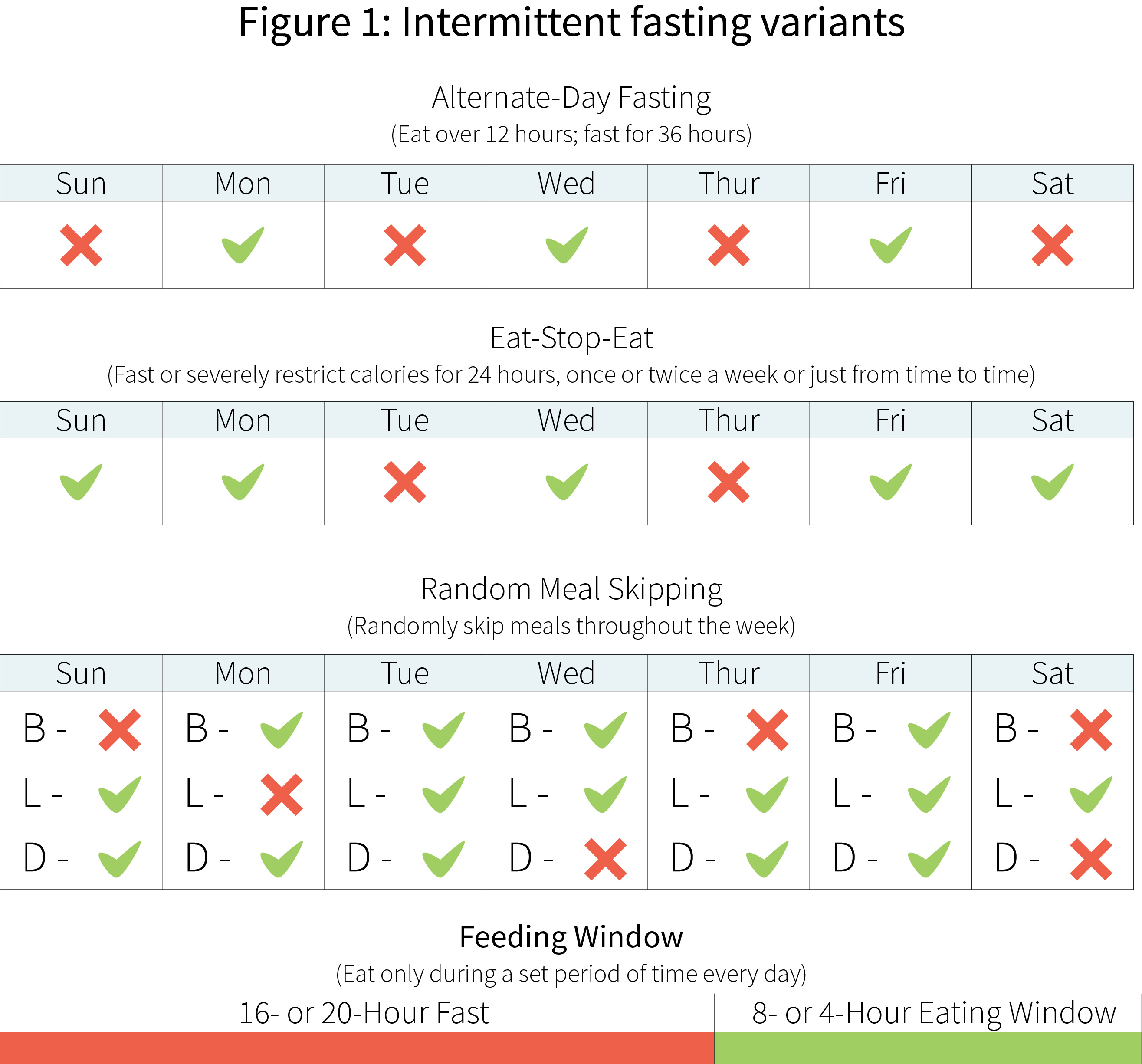

- Alternate-Day Fasting (also known as Alternate-Day Modified Fasting). This diet can take different forms: you can eat over 12 hours then fast for 36 hours; you can eat over 24 hours then fast for 24 hours; or you can eat normally over 24 hours then eat very little (about 500 kcal) over the next 24 hours.

- Eat-Stop-Eat. You fast or severely restrict calories for 24 hours, either at regular intervals (two days per week in the 5:2 Diet) or just from time to time.

- Random Meal Skipping. You skip meals at random throughout the week.

- Feeding Window. You can only eat during a set period of time every day (from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m, for instance).

Should you decide to try intermittent fasting, pick a variant you think you can stick with for at least a few weeks.

Effects on weight

Yes, IF works, though to very different degrees in different studies.[2] This variability could be explained by different factors, among which is the specific IF variant studied. For instance, simply skipping breakfast led to some weight loss in one study[3] but not in another.[4] In each of those two studies, the control group was provided with a standard breakfast, such as oatmeal, but neither group was restricted in what they could eat the rest of the day.

It’s also possible that people with more weight to lose may benefit more from an IF approach, but one thing is sure: if you compensate for the meals you skipped by eating more later in the day, or the next day, or the next, you won’t lose weight. The weight-loss equation is simple: you need to ingest less calories than you burn. IF is just one way to make this happen, but it is a way that some people find easier than the more common “eat smaller meals” approach.

To lose weight, you need to burn more than you eat — or, conversely, to eat less than you burn. Some people find this goal easier to reach through intermittent fasting than through the traditional “smaller meals” approach.

Effects on health

The body of evidence on IF in humans is still relatively small,[5] but a number of studies have reported improvements in various health markers aside from weight, notably lipids.[1] It is still an active area of debate if there are any unique metabolic benefits to IF over chronic caloric restriction (CCR, the traditional “eat smaller meals” approach).

The most intriguing of these debated benefits is a prolonged life. It has long been known that caloric restriction in general (i.e., CCR and IF both) can slow the aging process and extend lifespan in many animal models,[6][7] due in part to its kick-starting some regenerative processes.[6] Keep in mind, however, that those animals were either fed low-calorie diets or rotated through periods of fasting for most of their lives. It is still not known if IF can reliably produce greater life-extension over CCR in animal models,[1][8] let alone in humans, and if it can, which variant is best and how many weeks, months, or years are required to make a difference.

Assessing the potential metabolic benefits of CCR and IF is a long-term endeavor, and IF is still very new. It may provide unique metabolic benefits over CCR,[1] as well as mood benefits,[9] but solid research is still sparse, so that “further research in humans is needed before the use of fasting as a health intervention can be recommended.”[10]

Preliminary evidence suggests that fasting could have unique metabolic benefits, including life extension, but those need to be confirmed by further research in humans.

Other considerations

Depending on the length of your fast, you may experience stress, headaches, constipation, or dehydration. Staying hydrated is particularly important; it’ll also help mitigate any headaches or constipation.

Some preliminary evidence suggests that a periodic reduction of caloric intake may produce physiological benefits similar to those of fasting. A fast-mimicking diet is a strategy where, instead of completely forgoing food, you simply consume a low-calorie diet for 5 days straight each month.[11] The typical protocol entails eating 1,090 kcal (10% protein, 56% fat, 34% carb) on the first day, then 725 kcal (9% protein, 44% fat, 47% carb) on each of the next four days.

Keep in mind that IF is not for everyone. People with impaired glycemic control should avoid fasting, as it causes poorer glucose response.[12] Also, if you’re pregnant, underweight, younger than 18, or have a history of disordered eating, IF is probably not for you.

Intermittent fasting is a viable strategy to slim down or maintain a healthy weight. In that respect, however, continual caloric restriction (the traditional “eat smaller meals” diet) offers similar benefits. What matters most is consistency. People who find eating less often easier than eating less could especially benefit from trying IF. As for unique metabolic health benefits of fasting … the debate is still ongoing.

References

- ^Mattson MP, Longo VD, Harvie MImpact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processesAgeing Res Rev.(2016 Oct 31)

- ^Tinsley GM, La Bounty PMEffects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humansNutr Rev.(2015 Oct)

- ^Geliebter A, Astbury NM, Aviram-Friedman R, Yahav E, Hashim SSkipping breakfast leads to weight loss but also elevated cholesterol compared with consuming daily breakfasts of oat porridge or frosted cornflakes in overweight individuals: a randomised controlled trialJ Nutr Sci.(2014 Nov 13)

- ^Betts JA, Richardson JD, Chowdhury EA, Holman GD, Tsintzas K, Thompson DThe causal role of breakfast in energy balance and health: a randomized controlled trial in lean adultsAm J Clin Nutr.(2014 Aug)

- ^Ganesan K, Habboush Y, Sultan SIntermittent Fasting: The Choice for a Healthier LifestyleCureus.(2018 Jul 9)

- ^Speakman JR, Mitchell SECaloric restrictionMol Aspects Med.(2011 Jun)

- ^Mercken EM, Carboneau BA, Krzysik-Walker SM, de Cabo ROf mice and men: the benefits of caloric restriction, exercise, and mimeticsAgeing Res Rev.(2012 Jul)

- ^Longo VD, Antebi A, Bartke A, Barzilai N, Brown-Borg HM, Caruso C, Curiel TJ, de Cabo R, Franceschi C, Gems D, Ingram DK, Johnson TE, Kennedy BK, Kenyon C, Klein S, Kopchick JJ, Lepperdinger G, Madeo F, Mirisola MG, Mitchell JR, Passarino G, Rudolph KL, Sedivy JM, Shadel GS, Sinclair DA, Spindler SR, Suh Y, Vijg J, Vinciguerra M, Fontana LInterventions to Slow Aging in Humans: Are We Ready?Aging Cell.(2015 Aug)

- ^Hussin NM, Shahar S, Teng NI, Ngah WZ, Das SKEfficacy of fasting and calorie restriction (FCR) on mood and depression among ageing menJ Nutr Health Aging.(2013)

- ^Horne BD, Muhlestein JB, Anderson JLHealth effects of intermittent fasting: hormesis or harm? A systematic reviewAm J Clin Nutr.(2015 Aug)

- ^Wei M, Brandhorst S, Shelehchi M, Mirzaei H, Cheng CW, Budniak J, Groshen S, Mack WJ, Guen E, Di Biase S, Cohen P, Morgan TE, Dorff T, Hong K, Michalsen A, Laviano A, Longo VDFasting-mimicking diet and markers/risk factors for aging, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular diseaseSci Transl Med.(2017 Feb 15)

- ^Jakubowicz D, Wainstein J, Ahren B, Landau Z, Bar-Dayan Y, Froy OFasting until noon triggers increased postprandial hyperglycemia and impaired insulin response after lunch and dinner in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trialDiabetes Care.(2015 Oct)