Stuart Phillips’ group at McMaster University has been conducting research on all things protein for close to two decades, with particular emphasis on how protein feeding affects protein synthesis at the whole-body level, as well as specifically in the muscle tissue (obtained from muscle biopsy specimens).

Measuring protein synthesis (or degradation) in muscle is the best biomarker of ongoing muscle anabolism or catabolism that exists. Protein synthesis during weight loss is important since keeping muscle on helps regulate blood sugar and keeps metabolism higher[1]. Obtaining information about fat or protein turnover at a particular point in time can tell us how well the body is conserving lean mass during weight loss, which is what this study intended to do.

Who and what was studied?

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of whey and soy supplementation on protein synthesis and biomarkers of lipolysis during weight loss, with carbohydrate supplementation as the control. Even though body composition was measured during this study, the effect of whey or soy protein supplementation on body composition was not a major endpoint of the study. This was likely due to the relatively short duration of the study, as small body composition changes would not be detectable even with DXA (Dual X-ray Absorptiometry) measurements, which the study uses and is considered the gold standard for body fat measurement. Previous research has shown the error from DXA to be around 1.2%[2], which would eclipse the relatively minor body composition changes from this study (see also: Measuring body fat percentage: It's an accuracy thing.

There have been many studies comparing the effects of soy and whey protein in stimulating protein synthesis and affecting body composition in a range of conditions, but few that have looked specifically into the effect on protein synthesis and lipolysis during weight loss.

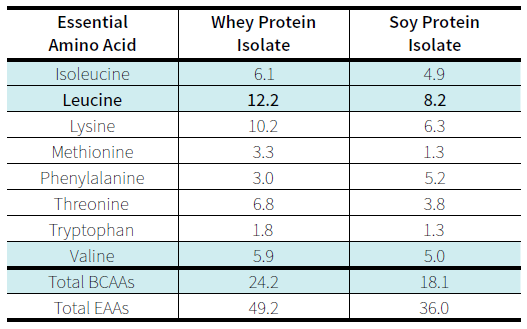

The studies that have previously compared whey to soy in their ability to stimulate protein synthesis and stimulate gross muscle hypertrophy in other contexts have generally found whey to be superior to soy[3]. As seen in the figure below, this is probably due to whey having a more complete amino acid profile (most soy is very low in two of the essential amino acids, methionine and lysine) and especially due to whey’s higher leucine content, which is the major factor protein’s ability to stimulate protein synthesis.

In order to examine the effects of soy or whey on protein synthesis during weight loss, 40 healthy, overweight and obese participants (19 males and 21 females) were included and randomized to to receive either a twice daily whey supplement (27 grams per supplement), soy protein supplement (26 grams per supplement) or carbohydrate (CHO) controls (25 grams per supplement), resulting in a total daily protein intake of 1.3 grams per kilogram of bodyweight in the protein-supplemented groups and 0.7 grams per kilogram of bodyweight in the CHO group. All food was provided by the research team in the form of prepackaged meals, to increase compliance.

During the study, all participants were first put on a three-day maintenance diet (given maintenance calories and 1 gram per kilogram of body weight of protein), subjected to the first test day, and then put on 14 days of a hypocaloric diet, followed by the second test day. The purpose of the maintenance diet was to equilibrate the subjects and put them on even ground, metabolically speaking. The hypocaloric diet was calculated to provide an energy deficit of 750 kcals per day, which should result in a weight loss of one to three kilograms over the course of 14 days. On both of the test days, the subjects received stable isotope infusions with isotope-labelled phenylalanine and glycerol, were DXA scanned, and had blood and muscle samples taken.

Body composition (total, fat and lean mass) was obtained from DXA scans. Muscle protein synthesis was calculated from tissue enrichment of stable isotope labelled phenylalanine in muscle samples. Lipolysis (fat burning) was calculated using the appearance of the isotope-labelled glycerol in the blood. Glucose and insulin levels were obtained from blood samples.

Overweight and obese participants were randomized to receive either soy or whey protein, or a carbohydrate control, and put on a hypocaloric diet. Body composition measurements and muscle protein synthesis were measured and compared between groups.

What were the findings?

The researchers found no significant difference in body composition between the groups. This was actually the expectation for a study of this duration and diet composition.

It has been shown numerous times that whey is a so-called “fast” protein[4], which means that the amino acids in it are absorbed faster than other proteins with a similar amino acid content. In this study we see this yet again, as release of leucine, essential amino acids and total amino acids were significantly higher after ingestion of whey protein than after soy. Soy still outperformed the CHO control supplement. In fact, the plasma leucine release (measured by the area under the curve AUC) from whey was almost three times higher than that for soy, whereas the essential and total amino acid AUC’s were approximately twice as high.

Not surprisingly, there were also differences in insulin and glucose concentrations following ingestion of the supplement between protein groups and the CHO control group, both before and after the dietary intervention. Ingesting the glucose control supplement resulted in higher glucose and insulin levels than ingesting either protein supplement, with no difference between soy and whey protein supplementation groups. As amino acids are absorbed more rapidly into the bloodstream from whey protein than soy protein, it is plausible to expect higher blood glucose and insulin levels after whey supplementation.

There was also a significant difference between the amount of circulating glycerol between the protein groups and the CHO control group. Glycerol was lower in the CHO group than in either protein group. This indicates that lipolysis is suppressed following CHO ingestion relative to both of the protein groups. In the post-prandial condition, the amount of glycerol in the blood is a measure of the rate of ongoing lipolysis. Fat is stored as triglycerides, and when fat stores receive neuroendocrine signals to mobilize fat, triglycerides are hydrolyzed into fatty acids and glycerol, both of which are released to the circulation. The fatty acids are metabolized in most of the body, whereas most of the glycerol is used for gluconeogenesis. The most likely explanation for the lower glycerol levels observed following CHO ingestion is probably that insulin strongly inhibits lipolysis. Since it was shown that the CHO supplement resulted in higher insulin, this further reinforces this hypothesis.

The main finding of the study was the effect of the protein supplements on protein synthesis in the myofibrillar protein fraction of muscle (the so-called Fractional Protein Synthesis, FPS), before and after the dietary intervention.

The researchers measured FPS before and after protein ingestion, as well as before and after the dietary intervention. The baseline FPS was around 0.02-0.03%/hour, but upon stimulation it increased to 0.06-0.07%/hour for whey and 0.03-0.04% for soy. When the FPS was expressed as the change in FPS from before to after supplement ingestion, soy scored higher than the CHO control supplement and whey scored higher than both. This means that whey stimulates the protein synthesis in muscle more efficiently than soy protein does.

Whey protein was absorbed more quickly than soy protein, and stimulated muscle protein synthesis by roughly two times the amount that soy supplementation did. However, no differences in overall body composition was observed between the groups.

The big picture

The results regarding amino acid, glucose, insulin, and glycerol concentrations were in line with numerous previous observations.

When it comes to the findings for body composition, this study actually does not prove that whey is superior for maintaining lean mass during weight loss. There’s a fair chance that whey probably is better, but that cannot be determined from these results because this study lacks statistical power to find such differences.

In order for differences between groups to manifest as statistically significant, a sufficient number of subjects must be enrolled. If the between-group difference we are looking at is small relative to the variation in the observations, this calls for more subjects. The study duration was short (14 days) and therefore the changes in lean and fat mass are small compared to the margin of error using a DXA scanner, meaning that if any difference did exist between groups, it would have taken more participants or a longer study duration for significant changes to manifest.

If you know the variation in the measurement you are doing, you can actually calculate the number of subjects needed to detect a group difference of a given size. This is called a power analysis. The researchers actually describe that they knew they had inadequate power to detect between-group differences, which was acceptable as this was not part of the primary objective for the study. Alternatively, this may be a real and valid finding. It is possible that although one protein source may be more effective than another in a short window of time for measuring FPS, overall dietary intake may be most important for producing long-term adaptations in body composition.

What the study did show, however, was that whey stimulates protein synthesis in myofibrillar proteins much more efficiently than soy protein supplementation. How this translates into lean mass sparing during weight loss is very hard to derive for numerous reasons. FPS is normally used as a surrogate biomarker for a snapshot of hypertrophy processes. However, hypertrophy or atrophy is the result of net protein synthesis or degradation, which is again the product of gross protein synthesis and net protein degradation. Therefore, it should be apparent that modulation of protein degradation is just as important as modulation of protein synthesis. This is supported by the results of some studies[5], which have shown that different protein sources may have different influences on protein synthesis and degradation.

The reason that protein synthesis is more frequently reported is that the technology for measuring protein synthesis is much better than the technology available for measuring protein degradation. All of these factors make it difficult to conclusively state whey’s superiority over soy based on this study. The protein synthesis measurement used in this study is a surrogate for the effect on muscle mass. But changes in muscle mass can be measured directly with something like DXA, albeit this requires a more challenging study setup, meaning more subjects for longer time and a higher study cost. Of course, studies can always be better or more detailed, so maybe this study will be the springboard for the next, more detailed study.

Lastly, funding for this study was provided by the Dairy Research Institute through the Whey Protein Research Consortium. However, the reported findings are in agreement with the literature and with other studies not supported by dairy farmer’s associations.

Frequently asked questions

How much daily protein synthesis and degradation happens normally, and under weight loss or muscle gain conditions?

Baseline fasted FPS in this study was around 0.02-0.03%/hour, whereas the fed FPS was two to three times higher. Based upon these numbers, and MPS and FPS data recorded elsewhere in the literature, we can assume an average total protein synthesis of 1.0-1.5%/day.

This means that 1.0-1.5% of the protein of the muscle protein is built up and broken down per day at muscle mass equilibrium. The amount of muscle made out of protein is constant, at around 20% of the wet weight of muscle. As a normal adult (60-80 kilograms / 130-175 pounds) carries 30-40% of his or her body weight as muscle mass, this corresponds to 200-400 grams of muscle (or 40-80 grams of muscle protein) that is built up and broken down, daily.

In the context of changes in muscle mass during sustained weight loss or resistance training, the net changes in muscle mass are generally on the order of 10-50 grams per day. These can be bigger at the onset of weight loss or weight gain, but it still underscores that much more protein is being built up and broken down on a daily basis, than that which is ultimately gained or lost as hypertrophy or atrophy.

Has there been research connecting muscle protein synthesis to the end result of muscle hypertrophy?

A previous paper[6] from Phillips’ research lab compared the protein synthesis measured following a resistance exercise bout in a part of a chronic resistance training study with the gross hypertrophy measured after 16 weeks of the resistance exercise program. The researchers found no correlation between the two measures. Even though that was in a training study, the result underscores that maybe using protein synthesis is not as good of a biomarker as we sometimes would like to think.

What about molecular biology markers of muscle gain and loss -- do they have similar findings as muscle protein synthesis?

It is also worth noting that there is a disconnect[7] between protein synthesis measurements and several molecular biology biomarkers, such as insulin signaling through the Akt/mTOR signaling cascade or FOXO transcription factor expression. In this case, however, this is more likely caused by the poor reliability of the molecular biology biomarkers, as they can display anabolic signaling even in grossly catabolic cachectic subjects[8].

What should I know?

Ingestion of whey protein stimulates myofibrillar protein synthesis during weight loss more efficiently than soy protein and naturally better than carbohydrate. This indicates that protein obtained from whey may more efficiently spare muscle mass than protein from soy, but the actual impact is outside the capabilities of this study to assess.

References

- ^Wolfe RRThe underappreciated role of muscle in health and diseaseAm J Clin Nutr.(2006 Sep)

- ^Cordero-MacIntyre ZR, Peters W, Libanati CR, España RC, Abila SO, Howell WH, Lohman TGReproducibility of DXA in obese womenJ Clin Densitom.(2002 Spring)

- ^Phillips SMThe science of muscle hypertrophy: making dietary protein countProc Nutr Soc.(2011 Feb)

- ^Dangin M, Boirie Y, Guillet C, Beaufrère BInfluence of the protein digestion rate on protein turnover in young and elderly subjectsJ Nutr.(2002 Oct)

- ^Boirie Y, Dangin M, Gachon P, Vasson MP, Maubois JL, Beaufrère BSlow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretionProc Natl Acad Sci U S A.(1997 Dec 23)

- ^Mitchell CJ, Churchward-Venne TA, Parise G, Bellamy L, Baker SK, Smith K, Atherton PJ, Phillips SMAcute post-exercise myofibrillar protein synthesis is not correlated with resistance training-induced muscle hypertrophy in young menPLoS One.(2014 Feb 24)

- ^Greenhaff PL, Karagounis LG, Peirce N, Simpson EJ, Hazell M, Layfield R, Wackerhage H, Smith K, Atherton P, Selby A, Rennie MJDisassociation between the effects of amino acids and insulin on signaling, ubiquitin ligases, and protein turnover in human muscleAm J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.(2008 Sep)

- ^Jespersen JG, Nedergaard A, Reitelseder S, Mikkelsen UR, Dideriksen KJ, Agergaard J, Kreiner F, Pott FC, Schjerling P, Kjaer MActivated protein synthesis and suppressed protein breakdown signaling in skeletal muscle of critically ill patientsPLoS One.(2011 Mar 31)