While there are theories that MS prevalence is related to lifestyle factors, such as vitamin D status, other researchers have examined the disease through the lens of the “hygiene hypothesis”, the popular idea that modern society’s germophobia and obsession with sanitation have caused immune systems to overreact and develop allergies or autoimmunity.

Some researchers believe that humans have altered the natural environment for[1] the billions of bacteria living in our guts in a quest for cleanliness. It is possible that this altered microbiome is associated with the increase in some autoimmune diseases that has been observed over the past half century.

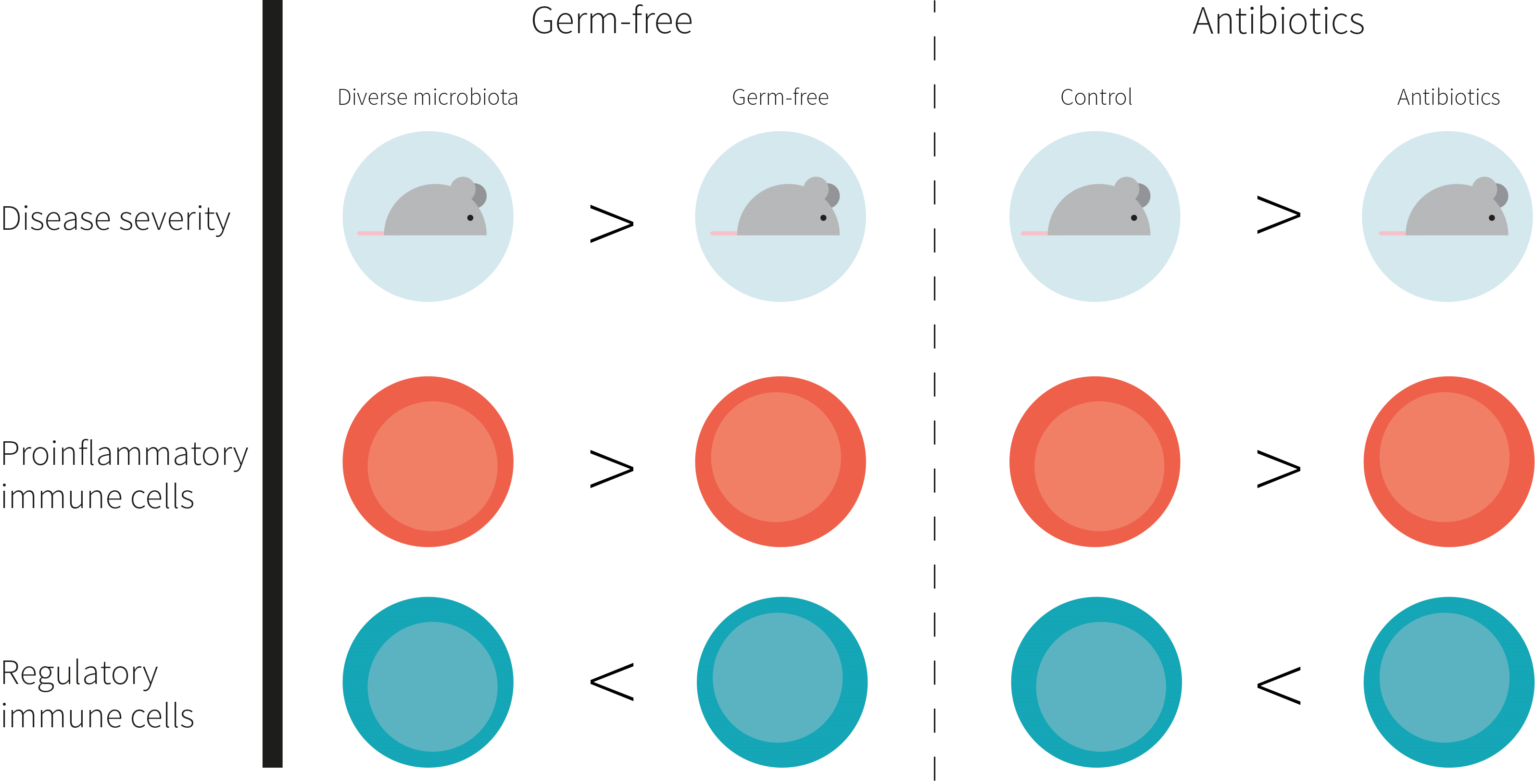

Furthermore, it has been established that there is a gut-brain connection[2] between microbiota and the central nervous system (CNS), and cross-talk between them affects a wide variety of bodily processes, from food intake to mood. Researchers have also shown a clear link between manipulation of gut microbiota in mice and the development and progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a disease induced in mice to study CNS inflammation and degeneration similar to that experienced by humans with MS. As shown in Figure 1, germ-free mice and those treated with antibiotics experienced delayed onset of EAE. Additionally, mice fed oral probiotics experienced varying effects on disease progression, both beneficial and harmful, depending on the strain.

Figure 1: Mice and EAE, non-probiotic observations

Reference: Wang, Y, Kasper, L. Brain Behav Immun. 2014 May.

However, successful pharmacological mouse treatments extended to human trials have had mixed results. While a few were effective, some exacerbated illness in study participants.