Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impaired social communication and repetitive behavior patterns. While the exact pathology of ASD is unknown, there may be a connection between diet and ASD behavioral symptoms.

Many dietary supplements have been investigated as potential treatments, including omega-3 fatty acids,[1] melatonin,[2] vitamin-d,[3] and a combination of vitamin-b6 and magnesium;[4] but the gluten-free and casein-free (GFCF) diet has become one of the more popular interventions among parents with ASD children.

Survey have shown that anywhere from 20% to 70% of respondents[5] have tried a GFCF diet. Parents often report symptom improvement when placing their children on this diet,[6] but what do results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) tell us?

Many families try decreasing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) symptoms with a gluten-free, casein-free (GFCF) diet. Several trials have been conducted to examine this connection.

What is the theory behind the GFCF diet?

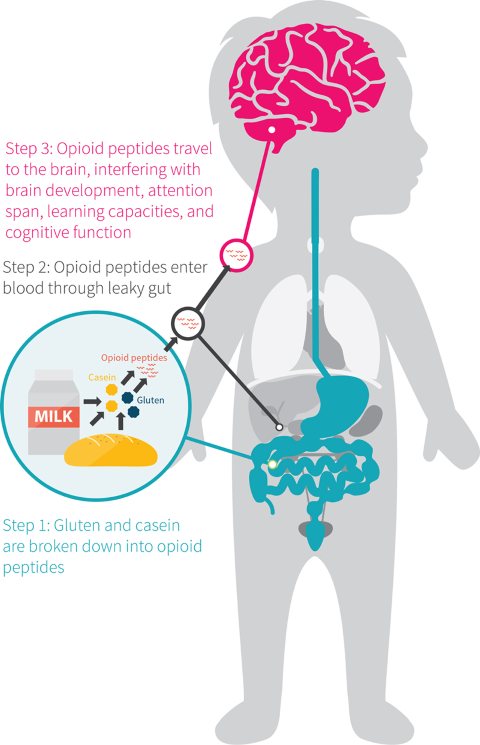

The opioid-excess theory of ASD has long been a popular hypothesis for explaining how a GFCF diet may alleviate ASD behavioral symptoms.[7] It has three main components:

-

The incomplete breakdown of the proteins making up gluten and casein can form excess opioid peptides.

-

These peptides can enter the body through an abnormally permeable intestinal border, which is speculated to be more common in people with ASD.[8]

-

If produced in sufficient quantities, these peptides could theoretically cross the blood–brain barrier and interfere with normal brain development.[8]

This hypothesis, however, is being disputed. Some studies did report greater gut permeability in people with ASD,[9][10] but others saw no difference.[11] Moreover, highly sensitive measurement techniques consistently failed to find detectable concentrations of opioid peptides in the urine samples of patients with ASD.[12][13] If significant amounts of opioid peptides were making it past the gut and into the bloodstream, urine tests should reveal their high levels as the body worked to eliminate them.

According to the opioid-excess theory, the incomplete breakdown of gluten or casein (two proteins) can form opioid peptides that may exacerbate ASD symptoms. However, the literature does not consistently support this hypothesis.

What do GFCF studies show?

Since the 1970s, more than 30 trials have tried to ascertain the role a GFCF diet could play in ASD therapy, but many suffered from poor methodological quality.[5][14]

The trials often

- Were short in duration.

- Had small sample sizes.

- Lacked a control group.

- Were single-blinded or not blinded at all.

- Performed no power calculation.

Moreover, changes in behavior were usually reported only by the parents, yet in most trials, the parents knew which group (placebo or GFCF) their child was in. This knowledge introduced possible bias into the studies, since the parents who believed that the GFCF diet would benefit their child were more likely to report positive results even if there were none. Unconscious bias such as this can lead to false positives in a study’s findings.

To reduce the risk of bias, we’ll examine the most rigorously controlled GFCF trials currently available: those that are double-blinded, randomized, and placebo-controlled. At present, five such trials have been conducted.

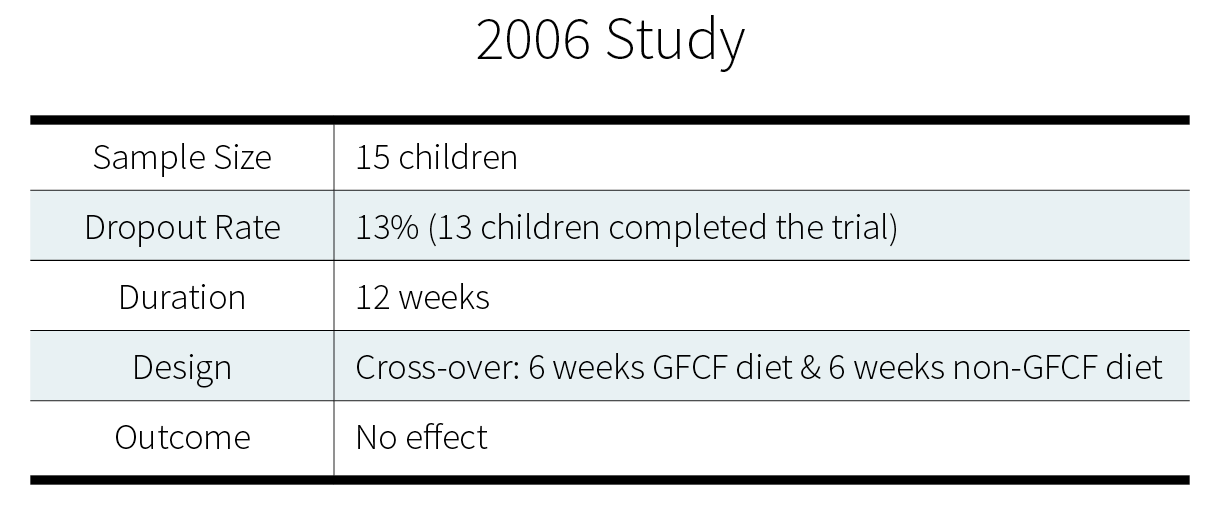

2006 Study

The gluten-free, casein-free diet in autism: results of a preliminary double-blind clinical trial.[15]

Standard assessment questionnaires were administered, such as the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) and the Ecological Communication Orientation Scale (ECOS). Both scales monitor the frequency of behavioral patterns, such as social initiating, social responding, intelligible words spoken, and non-speech vocalizations.

Additionally, research assistants videotaped the child interacting with their primary caretaking parent. Two independent coders, who were blinded to the dietary treatment status of the child, rated each taped assessment. No significant differences were observed for any of the behavioral endpoints measured between the GFCF diet and the control diet.

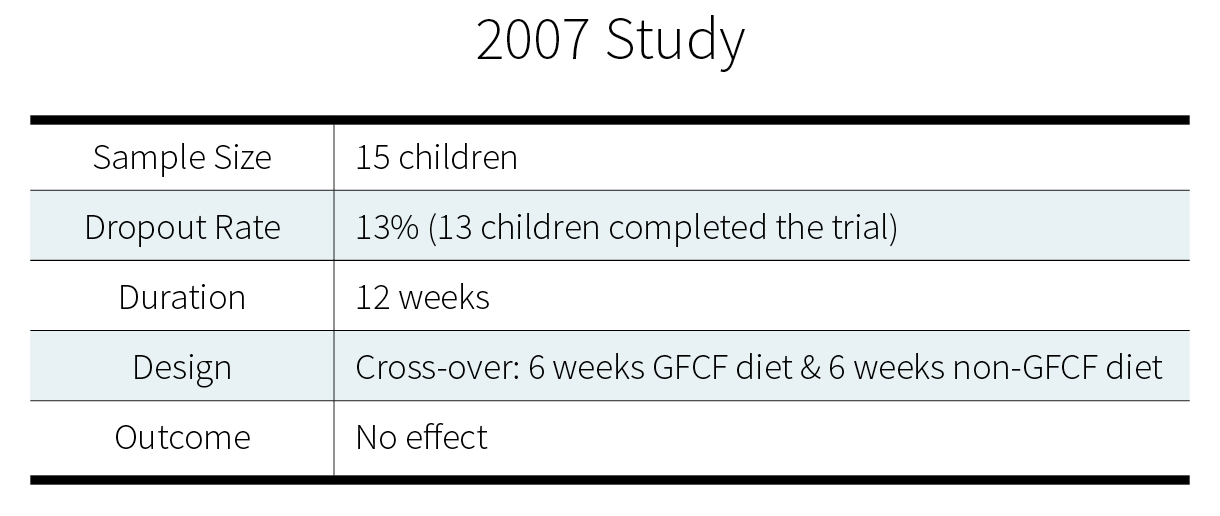

2007 Study

The gluten- and casein-free diet and autism: communication outcomes from a preliminary double-blind clinical trial.[16]

This study is a retrospective analysis of the “2006 Study” above. Its authors sought to perform a more in-depth analysis of the verbal and nonverbal communication outcomes than the one mediated by the ECOS scale, used in the original study. With this aim in mind, they re-evaluated the existing videotapes of parent-and-child interactions, with a focus on verbal communication. Again, however, no significant changes were observed between the GFCF diet and the control diet.

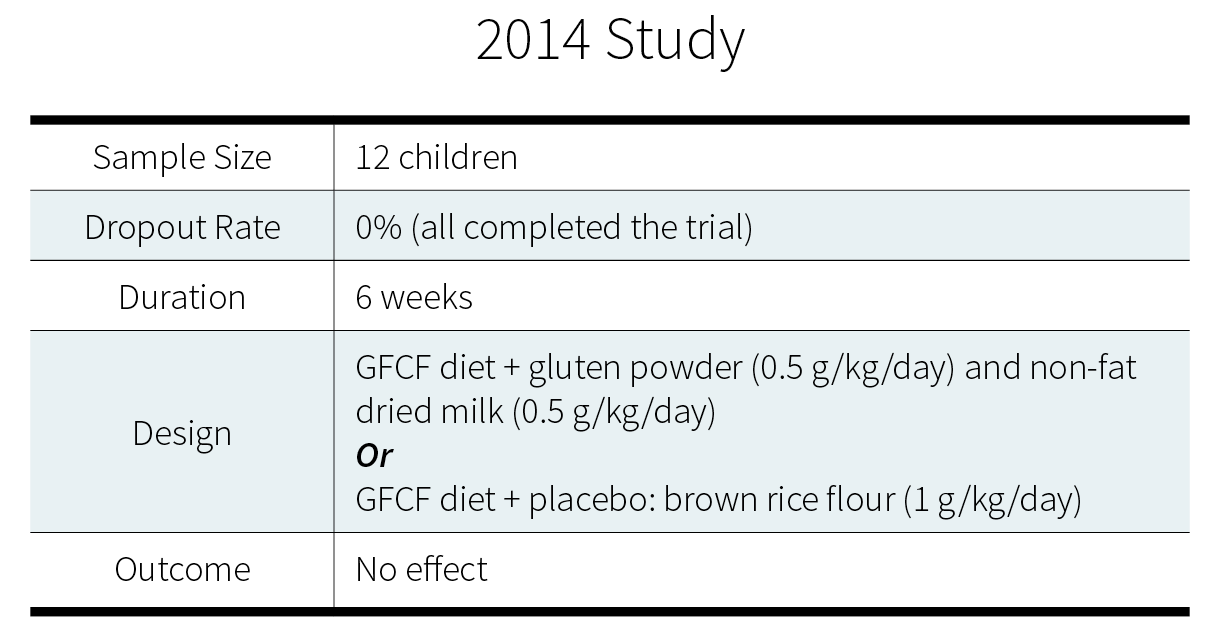

2014 Study

Are “leaky gut” and behavior associated with gluten- and dairy-containing diet in children with autism spectrum disorders?[17]

For the first 2 weeks, all participants followed a GFCF diet. For the remaining 4 weeks, they were randomized to the intervention group (brown rice flour) or the control group (gluten powder and non-fat dried milk). Blinded to the group a child was in, parents and investigators assessed hyperactivity, irritability, and inattention. No significant behavioral differences were observed between groups.

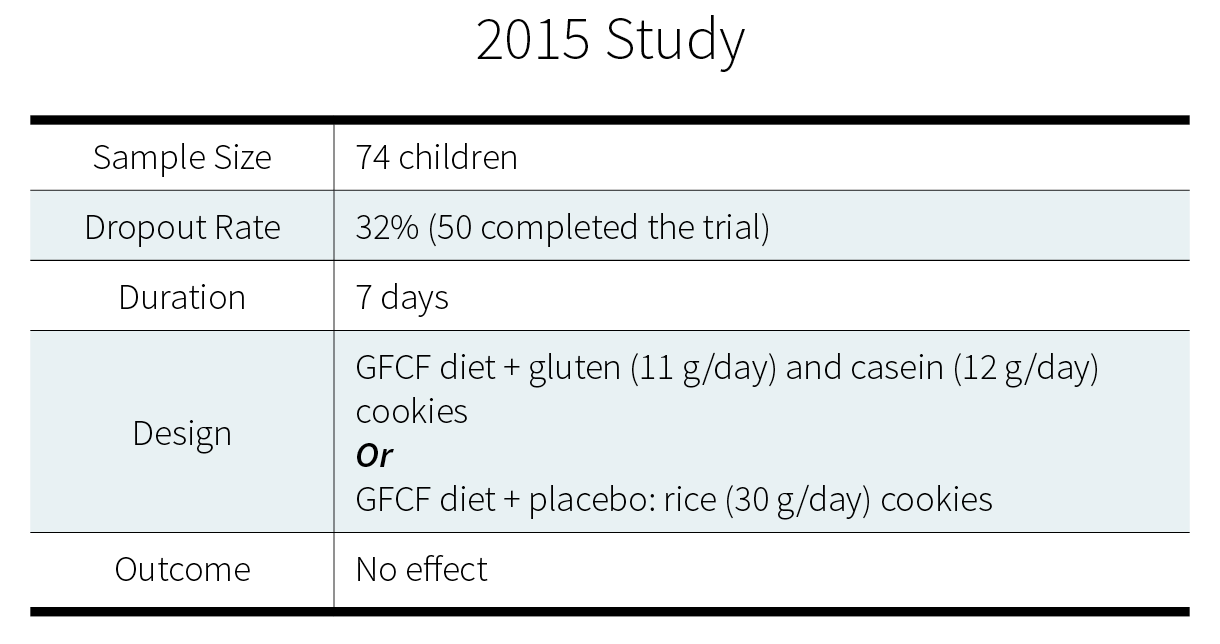

2015 Study

Gluten and casein supplementation does not increase symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder.[18]

Researchers used the Approach Withdrawal Problems Composite (AWPC) subtest of the Pervasive Developmental Disorder Behavior Inventory (PDDBI) to monitory maladaptive behavior before and after supplementation. In both groups, the AWPC score decreased significantly after supplementation. But the researchers noted that “the change in the degree of maladaptive behavior was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.971)” (emphasis added).

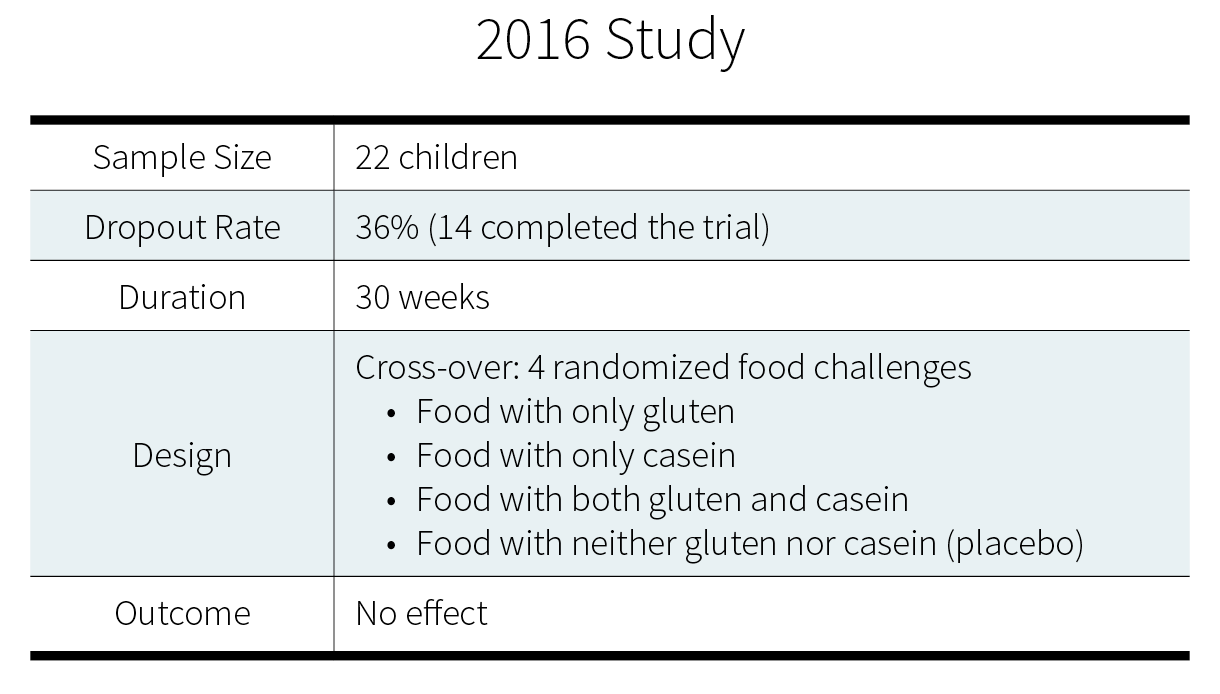

2016 Study

The gluten-free/casein-free diet: a double-blind challenge trial in children with autism.[19]

The main conclusion of this study was that the GFCF diet did not change measures of “physiologic function, behavioral disturbance (sleep disruption and over-activity), or ASD-related behaviors”. The researchers also examined the children’s individual data to see if any individual results were being masked by the overall group result, but again found no clear pattern suggesting that the dietary challenge had had any effect, positive or negative, on any of the behavioral outcomes measured. A subset of children actually experienced fewer negative social relationship symptoms on the days gluten and casein were co-administered, but this trend never reached statistical significance.

Conclusion

Five double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials examining a total of 89 children have found that a GFCF diet did not improve ASD behavior symptoms.

Is GFCF the best therapy for ASD? Unlikely.

Two recent systematic reviews[20][21] and a consensus report by the American Academy of Pediatrics[22] have concluded that cutting out gluten and casein isn’t likely to help in the treatment of ASD.

Anecdotal reports of improvement could be due to casein- and gluten-free diets accompanying some other treatment or some healthy lifestyle habits. The potential benefits of other, more comprehensive diet changes have not been rigorously tested.

Given the current lack of evidence that a GFCF diet benefits people with ASD, emphasis on behavioral therapies is likely to provide greater benefit.[23][24]

A GFCF diet is unlikely, at least one its own, to improve the behavior of children with ASD. Time, energy, and resources may be better spent pursuing other treatment options.