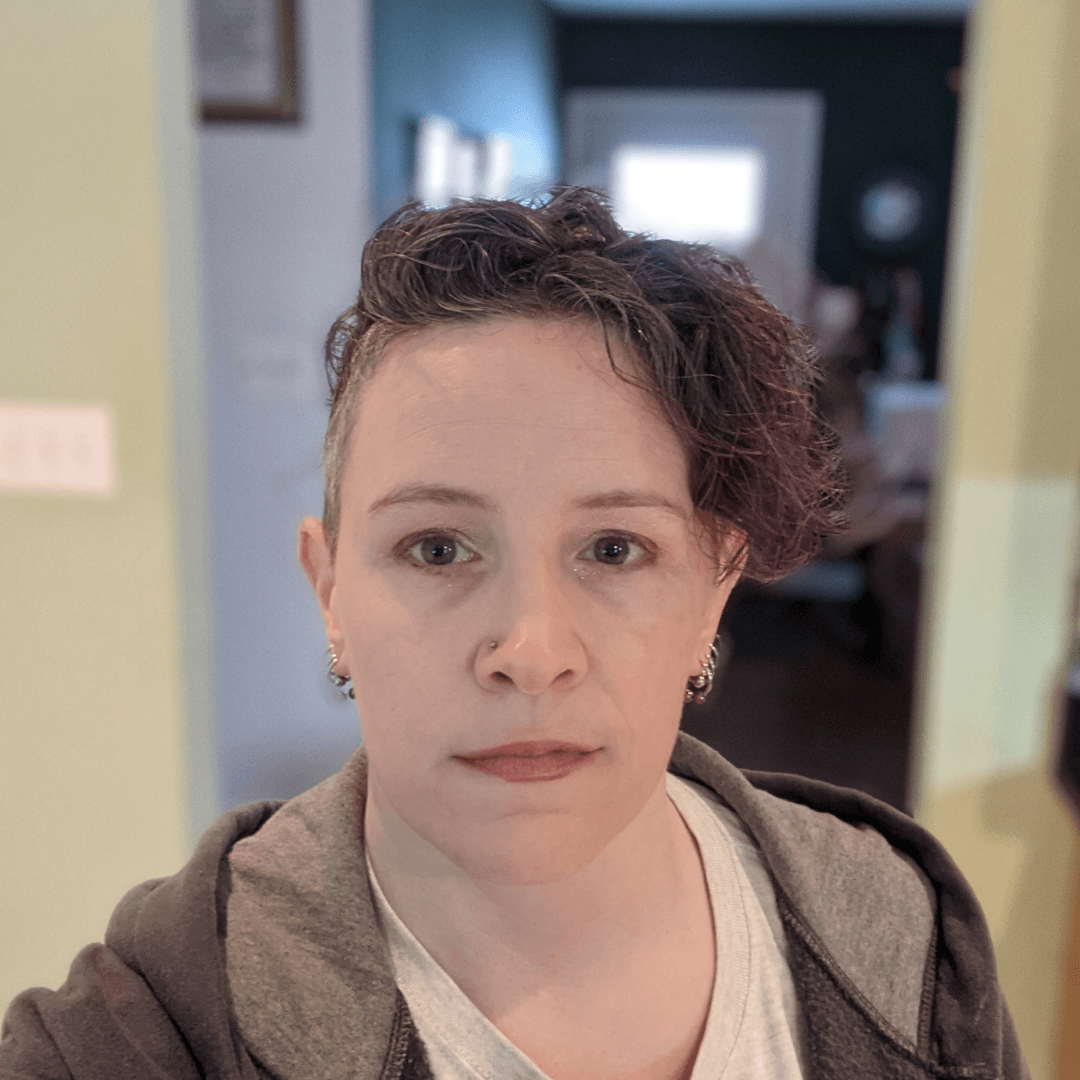

When measured acutely, moderate doses of alcohol (0.83g/kg) in resistance trained men when consumed immediately after exercise (where nothing was eaten 3.5 hours before, food given during drinking ab libitum) failed to note any significant differences in testosterone levels for up to 300 minutes after exercise[59] and another sports related study using 1g/kg after a simulated rugby match failed to note a decrease in testosterone despite noting a reduction in power output.[60] A third study using that did not pair ethanol with exercise but used a low dose of 0.45g/kg on three separate pulses 90 minutes apart noted that although there was a trend (via the circadian rhythm) for testosterone to increase in this study that it did not differ between ethanol and water intake.[61]

Conversely, a slightly lesser intake (0.5g/kg) has been shown to actually increase circulating testosterone from 13.6nmol/L to 16nmol/L (+17%) 2 hours after ingestion (which normalized by 4 hours), and inhibiting ethanol metabolism with 4-methylpyrazole (alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitor) by 37+/-3% and thus increasing the time ethanol could act abolished the increase in testosterone.[62] This increase in testosterone after 0.5g/kg has also been noted in premenopausal women,[63] and suggested to be act vicariously through the increased NADH/NAD+ ratio in the liver after these doses. Steroid metabolism and REDOX couplets interact in the liver,[64] where an increased rate of 17β-HSD type 2 enzyme and its conversion of androstenedione to testosterone is observed due to the increased NADH relative to NAD+ observed after ethanol intake, and this also explains the reduction in androstenedione observed in studies where testosterone is increased[63][64] and may help explain the increased levels of androstenedione in studies where testosterone is suppressed, where androstenedione may be increased by up to 54% (and dehydroepiandrosterone by 174%) 12 hours after large intakes of alcohol.[65]

That being said, another study using 0.675g/kg noted that testosterone increased and was more sensitive to being increased by gonadotropin releasing hormone, suggesting multiple pathways may be at play.[66] Red Wine may also confer additional benefits through its phenolic content, as Quercetin appears to be glucuronidated by the enzyme UGT2B17 in place of testosterone (sacrificial substrate) and may indirectly increase testosterone.[67] This study was in vitro, however, and Quercetin has low bioavailability.

Low to moderate doses timed around exercise have twice failed to demonstrate an increase or decrease in testosterone levels, with the increase being from a favorable change in the testosterone:androstenedione ratio in the liver (mimicking the NADH:NAD+ ratio, which is increased during alcohol consumption). Not all studies not this increase though, and some just note no significant changes at all

One study lasting 3 weeks with daily consumption of 30-40g alcohol in non-smoking and social drinkers noted a 6.8% decrease in circulating testosterone levels in men (n=10), with no significant effect in women.[68] At the end of the study, control had circulating testosterone measured at 16.4nmol/L while the alcohol group was measured at 15.3nmol/L.[68]

These low doses, when taken over a prolonged period of time, might decrease testosterone; the degree of suppression is not likely to be practically relevant, however

Higher doses of alcohol, 1.5g/kg (average dose of 120g), have been demonstrated to suppress testosterone by 23% when measured between 10-16 hours after acute ingestion with no statistically significant difference between 3 and 9 hours of measurement.[69] It appeared, in this study, that alcohol suppressed a rise of testosterone that occurred in the control group which may have been based on the circadian rhythm.[69] Anothers study using an even higher dose (1.75g/kg over 3 hours) noted that over the next 48 hours that a small short-lived dip occurred at 4 hours, but a more statistically significant drop was seen at 12 hours which was mostly corrected by 24 hours (still significantly less than control) and completely normalized at 36 hours.[65] By 12 hours, the overall reduction in testosterone was measured at 27% while the overall decrease in testosterone at 24 hours was 16%.[65] Finally, a third study using 100-proof vodka at a dose of 2.4ml/kg bodyweight in 15 minutes (to spike blood alcohol concentration (BAC) up to 109+/-4.5mg/100mL, similar to the aforementioned 1.75g/kg study) noted suppressed testosterone levels correlating with the peak BAC, observed 84 minutes after ingestion.[70] This time delay seen in some studies, when put in social context, correlate with the observed lower serum testosterone levels seen with hangovers.[71] This study also noted that the changes in hormones were further from baseline in persons self-reporting a hangover, and less significant in persons without hangovers.[71]

Finally, an intervention in which alcohol was supplied intravenously (via catheter) to keep a breath alcohol level of 50mg% noted that free testosterone was suppressed at this level of intake in young (23+/-1) men only, with young women experiencing an increase in testosterone and older (59+/-1) men and women having no significant influences.[72] This correlates to a moderate dose of oral ethanol.

The mechanism of alcohol suppressing testosterone levels sub-chronically is via its actions as a testicular toxin, where it can reduce testosterone synthesis rates with no negative influence on the hypothalamus signals to the testes (if anything, a stimulatory effect occurs on the hypothalamus).[73][74]

Around the 1.5g/kg or higher ethanol intake, it appears that a subsequent dose-dependent decreasing of testosterone occurs and appears to occur with some degree of time delay up to 10 hours after consumption. One study using shots of vodka did note this suppression of testosterone occurring within 90 minutes though

In alcohol abusers, the chronic high intake of alcohol appears to be negatively correlated with circulating testosterone at rest; with longer duration and higher intakes of alcohol leading to less testosterone.[75]

Overall, alcohol can increase testosterone acutely through increasing a REDOX ratio in the liver (NADH:NAD+) but this spike is short lived; a reverse trend is seen at a later point when alcohol probably reaches the testicles to suppress testosterone synthesis, this is also short-lived for the most part. Chronic alcohol consumption at low doses is associated with a decrease in testosterone, but to a degree where it may not be practically relevant; alcoholism is associated with a larger and significant reduction in testosterone levels