What is vitamin K?

Vitamin K is an essential vitamin that plays an important role in blood coagulation, bone metabolism, and vascular health, and it is one of the four fat-soluble vitamins (along with vitamin A, vitamin D, and vitamin E).[10][11][12] Vitamin K is actually the collective term for several fat-soluble molecules called 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinones.[10][11][12]

There are two naturally occurring forms of vitamin K: vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) and vitamin K2 (menaquinones). K1 is the major dietary form and is found in several plant-based foods including spinach, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, collards, and soybeans.[6][10][11][12] Vitamin K2 is synthesized by bacteria — including gut bacteria in our microbiome — and is found in meat and fermented foods (e.g., nattō; fermented soybeans).[13][8][10][11][12]

Phylloquinone (vitamin K1) is the predominant form used in vitamin K supplements, but menaquinones (vitamin K2) are also used.[10][14] Another form of vitamin K called menadione (or vitamin K3) is an intermediate molecule in vitamin K metabolism.[10][12][15] It is not typically used in human supplements, but it is used in animal feed.[16]

What are vitamin K’s main benefits?

Due to vitamin K’s role in blood coagulation, bone metabolism, and vascular health,[10][11][12] supplementation with vitamin K is claimed to have a range of benefits on blood clotting (coagulation), bone health, cardiovascular health, diabetes and blood sugar, and cancer.

The main benefit of vitamin K supplementation is in newborn babies, because vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) can arise due to inadequate vitamin K storage or a vitamin K deficiency in the mother’s breast milk.[17][18][19][20] To reduce the risk of VKDB, a single 1-milligram (mg) intramuscular injection of vitamin K is routinely administered to newborns.[17][18][19][20] In adults, there is also a relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin K and normal blood coagulation.[21]

Observational studies have found that insufficient dietary intake of vitamin K (i.e., lower than the adequate intake) and low serum concentrations of vitamin K are associated with low bone mineral density.[22][23][24] It is also generally agreed that there is a relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin K and the maintenance of normal bone health.[21] However, while meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have found that supplementation with vitamin K can affect markers of bone health, including bone mineral density,[3] the effects on bone fracture risk are inconsistent.[4][5] Further research is needed to determine whether vitamin K can prevent or treat osteoporosis.

Low serum concentrations of vitamin K have been associated with coronary artery calcium progression, a marker of calcification and stiffening of arteries which can cause cardiovascular disease.[25] Consequently, vitamin K has been suggested to support cardiovascular health. However, while low serum concentrations of vitamin K appear to be associated with a greater cardiovascular disease risk and higher mortality,[26][27][26] the current evidence does not show a relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin K and the normal function of the cardiovascular system or cardiovascular disease mortality.[21][26] Furthermore, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials do not support a benefit of vitamin K supplementation on cardiovascular health.[28][29][30][31]

Low serum concentrations of vitamin K have also been associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes,[32] but randomized controlled trials show that the effect of supplementation with vitamin K on fasting glucose and insulin resistance is trivial and highly variable.[32][33][34]

Supplementation with vitamin K might play a role in cancer therapy, but further randomized controlled trials are needed to make firm conclusions.[35]

What are vitamin K’s main drawbacks?

While case studies have shown that injectable forms of vitamin K1 can cause allergic reactions[10][36][37] and that high doses of vitamin K3 can cause hemolytic anemia in some people,[10] the consumption of vitamin K is not associated with adverse effects or toxicity in the general population.[1][10][38][39] That said, vitamin K does interact with some drugs, including blood-thinning drugs (anticoagulants) like warfarin and drugs that affect the intestinal absorption of dietary fat, such as colesevelam and orlistat. People who use such drugs should consult their doctor before considering using a vitamin K supplement or altering their dietary intake of foods rich in vitamin K.

How does vitamin K work?

In humans, the main mechanistic role of vitamin K is in the γ-carboxylation of proteins called vitamin-K-dependent proteins. Several vitamin-K-dependent proteins have been identified, and they are primarily involved in the regulation of blood coagulation, vascular function, and bone metabolism.[10][40][11][12]

Supplementation with vitamin K can improve markers of bone health.[3][4][5] Evidence from animal studies and cell-culture studies shows that vitamin K can promote processes involved in bone formation (e.g., osteoblast differentiation and the carboxylation of osteocalcin), suppress processes involved in bone breakdown (e.g., osteoclast formation), and increase the concentration of enzymes (bone-specific alkaline phosphatase) and growth factors (IGF-1, GDF-15, etc.) involved in bone formation.[41][42][43]

What are other names for Vitamin K

- Phylloquinone (Phytomenadione; vitamin K1)

- Menaquinone-4 (MK-4

- Menatetrenone; vitamin K2)

- Menaquinone-7 (MK-7; vitamin K2)

- Menadione (sometimes called vitamin K3)

- Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)

Dosage information

Formulations:

- Phylloquinone (vitamin K1)

- Menaquinone-4 and menaquinone-7 (vitamin K2)

- Menadione (vitamin K3) is rarely used in supplements.

Range of dosages studied:

- Phylloquinone (vitamin K1): 0.1–10 mg per day (mg/day), equivalent to 100–10,000 micrograms (μg) per day.

- Menaquinone-4 (vitamin K2): 1–90 mg/day (1,000–90,000 μg/day).

- Menaquinone-7 (vitamin K2): 0.09–2 mg/day (90–2,000 μg/day).

Safety information:

Vitamin K interacts with several drugs, including blood-thinning (anticoagulant) drugs like warfarin and drugs that affect the intestinal absorption of dietary fat, such as colesevelam and orlistat. Vitamin K absorption and metabolism can be impaired in people with hepatobiliary dysfunction. A tolerable upper intake level (UL) for vitamin K has not been set, because there is insufficient data assessing the risk.[1][2] This does not mean that taking an amount higher than the recommended dose is safe, just that current data does not find adverse effects.

Dosage recommendation:

The dosages that have been found to improve markers of bone health are 0.1–5 mg/day (100–5000 μg/day) of phylloquinone (vitamin K1), 15–45 mg/day of menaquinone-4 (vitamin K2), or 100–375 μg/day of menaquinone-7 (vitamin K2).[3][4][5]

The adequate intake (AI) — the daily intake that ensures nutritional adequacy in most people — in micrograms (µg) per day for vitamin K is shown below.[1][2] Note that the AI for vitamin K varies slightly between countries; the data below are for the US.

| Age | Male | Female | Pregnancy | Lactation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 months | 2.0 µg/day | 2.0 µg/day | -- | -- |

| 7–12 months | 2.5 µg/day | 2.5 µg/day | -- | -- |

| 1–3 years | 30 µg/day | 30 µg/day | -- | -- |

| 4–8 years | 55 µg/day | 55 µg/day | -- | -- |

| 9–13 years | 60 µg/day | 60 µg/day | -- | -- |

| 14–18 years | 75 µg/day | 75 µg/day | 75 µg/day | 75 µg/day |

| Older than 18 years | 120 µg/day | 90 µg/day | 90 µg/day | 90 µg/day |

Vitamin K is found in several foods. High amounts per serving are found in spinach, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, collards, soybeans, etc.[6][7][8][9] Consult the FoodData Central database to check the amounts of vitamin K in the foods you eat.

Take with food: Yes. Intestinal absorption of vitamin K appears to be improved in the presence of dietary fat.[10]

Frequently asked questions

Vitamin K is an essential vitamin that plays an important role in blood coagulation, bone metabolism, and vascular health, and it is one of the four fat-soluble vitamins (along with vitamin A, vitamin D, and vitamin E).[10][11][12] Vitamin K is actually the collective term for several fat-soluble molecules called 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinones.[10][11][12]

There are two naturally occurring forms of vitamin K: vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) and vitamin K2 (menaquinones). K1 is the major dietary form and is found in several plant-based foods including spinach, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, collards, and soybeans.[6][10][11][12] Vitamin K2 is synthesized by bacteria — including gut bacteria in our microbiome — and is found in meat and fermented foods (e.g., nattō; fermented soybeans).[13][8][10][11][12]

Phylloquinone (vitamin K1) is the predominant form used in vitamin K supplements, but menaquinones (vitamin K2) are also used.[10][14] Another form of vitamin K called menadione (or vitamin K3) is an intermediate molecule in vitamin K metabolism.[10][12][15] It is not typically used in human supplements, but it is used in animal feed.[16]

The symptoms of vitamin K deficiency include bleeding disorders, impaired bone development, and spontaneous rash.[10][44] The signs of vitamin K deficiency include biomarkers of vitamin K status, such as low serum concentrations of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) and PIVKA-II (protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II).[45][44] PIVKA-II is an incompletely carboxylated form of prothrombin, which is a key protein involved in blood coagulation that is carboxylated by vitamin K.[45][44]

In newborn babies, a vitamin K deficiency can arise due to inadequate vitamin K storage or a vitamin K deficiency in the mother’s breast milk.[17][18][19][20] This can lead to a type of hemorrhage called vitamin K deficiency bleeding.

Vitamin K deficiency is not common in adults. Still, it can occur due to inadequate dietary intake or the use of drugs known to interfere with the absorption, metabolism, and synthesis of vitamin K (e.g., anticoagulants and drugs that affect the intestinal absorption of dietary fat).[10] It is also possible that antibiotics can inhibit the growth of vitamin-K-producing bacteria in the intestine and increase the risk of vitamin K deficiency.[10]

Vitamin K deficiency can also occur in people with hepatobiliary dysfunction or inflammatory bowel disease due to the impaired absorption and metabolism of vitamin K.

In women, severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy (known as hyperemesis gravidarum) and malnutrition during pregnancy can also cause vitamin K deficiency and lead to hemorrhage.[10][46][47]

Due to vitamin K’s role in blood coagulation, bone metabolism, and vascular health,[10][11][12] supplementation with vitamin K is claimed to have a range of benefits on blood clotting (coagulation), bone health, cardiovascular health, diabetes and blood sugar, and cancer.

The main benefit of vitamin K supplementation is in newborn babies, because vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) can arise due to inadequate vitamin K storage or a vitamin K deficiency in the mother’s breast milk.[17][18][19][20] To reduce the risk of VKDB, a single 1-milligram (mg) intramuscular injection of vitamin K is routinely administered to newborns.[17][18][19][20] In adults, there is also a relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin K and normal blood coagulation.[21]

Observational studies have found that insufficient dietary intake of vitamin K (i.e., lower than the adequate intake) and low serum concentrations of vitamin K are associated with low bone mineral density.[22][23][24] It is also generally agreed that there is a relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin K and the maintenance of normal bone health.[21] However, while meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have found that supplementation with vitamin K can affect markers of bone health, including bone mineral density,[3] the effects on bone fracture risk are inconsistent.[4][5] Further research is needed to determine whether vitamin K can prevent or treat osteoporosis.

Low serum concentrations of vitamin K have been associated with coronary artery calcium progression, a marker of calcification and stiffening of arteries which can cause cardiovascular disease.[25] Consequently, vitamin K has been suggested to support cardiovascular health. However, while low serum concentrations of vitamin K appear to be associated with a greater cardiovascular disease risk and higher mortality,[26][27][26] the current evidence does not show a relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin K and the normal function of the cardiovascular system or cardiovascular disease mortality.[21][26] Furthermore, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials do not support a benefit of vitamin K supplementation on cardiovascular health.[28][29][30][31]

Low serum concentrations of vitamin K have also been associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes,[32] but randomized controlled trials show that the effect of supplementation with vitamin K on fasting glucose and insulin resistance is trivial and highly variable.[32][33][34]

Supplementation with vitamin K might play a role in cancer therapy, but further randomized controlled trials are needed to make firm conclusions.[35]

While case studies have shown that injectable forms of vitamin K1 can cause allergic reactions[10][36][37] and that high doses of vitamin K3 can cause hemolytic anemia in some people,[10] the consumption of vitamin K is not associated with adverse effects or toxicity in the general population.[1][10][38][39] That said, vitamin K does interact with some drugs, including blood-thinning drugs (anticoagulants) like warfarin and drugs that affect the intestinal absorption of dietary fat, such as colesevelam and orlistat. People who use such drugs should consult their doctor before considering using a vitamin K supplement or altering their dietary intake of foods rich in vitamin K.

In humans, the main mechanistic role of vitamin K is in the γ-carboxylation of proteins called vitamin-K-dependent proteins. Several vitamin-K-dependent proteins have been identified, and they are primarily involved in the regulation of blood coagulation, vascular function, and bone metabolism.[10][40][11][12]

Supplementation with vitamin K can improve markers of bone health.[3][4][5] Evidence from animal studies and cell-culture studies shows that vitamin K can promote processes involved in bone formation (e.g., osteoblast differentiation and the carboxylation of osteocalcin), suppress processes involved in bone breakdown (e.g., osteoclast formation), and increase the concentration of enzymes (bone-specific alkaline phosphatase) and growth factors (IGF-1, GDF-15, etc.) involved in bone formation.[41][42][43]

Research is still scarce, but current evidence suggests that, through their effect on calcium regulation, some forms of vitamin K can help prevent osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases.

Vitamin K is poorly understood, both by the general public and among health professionals. It has a wide range of potential benefits, but their nature and extent are still uncertain.

Why is that?

Some vitamins are more popular than others. In the past, a lot of research went into vitamin C, which became a popular supplement. Nowadays, a lot of research goes into vitamin D, whose popularity as a supplement is steadily growing.

By contrast, research on vitamin K is still scarce, having slowly developed over the past two decades. Further, it is scattered, because there exist several forms of vitamin K. Some of those forms are present only in a few foods. Others exist in various foods, but only in minute amounts. Few have been the subject of human trials.

The human trials that do exist, however, are overall promising. In order to understand their value and limitations, first you need to know a few basic facts. So let’s begin:

What is vitamin K?

Of the four fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), vitamin K was discovered last. In 1929, Danish scientist Henrik Dam discovered a compound that played a role in coagulation (blood clotting).[48] When he first published his findings, in a German journal, he called this compound Koagulationsvitamin, which became known as vitamin K.

Today, we know that vitamin K participates in some very important biological processes, notably the carboxylation of calcium-binding proteins (including osteocalcin and matrix GLA protein).[49] In other words, vitamin K helps modify proteins so they can bind calcium ions (Ca2+). Through this mechanism, vitamin K partakes in blood clotting, as Henrik Dam discovered, but also of calcium regulation: it helps ensure that more calcium gets deposited in bones and less in soft tissues, thus strengthening bones and reducing arterial stiffness.

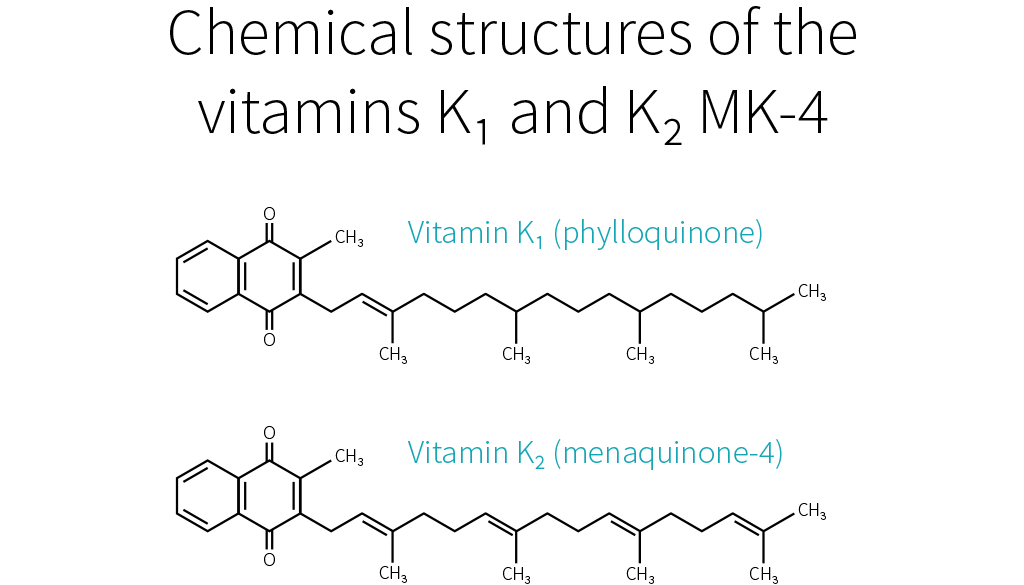

What complicates matters is that each vitamin has different forms, called vitamers, each of which may affect you differently. Vitamin K has natural vitamers, K1 (phylloquinone) and K2 (menaquinone), and synthetic vitamers, the best-known of which is K3 (menadione).

Vitamin K1

K1 is produced in plants, where it is involved in photosynthesis: the greener the plant, the greater its chlorophyll content; the greater its chlorophyll content, the greater its K1 content. When it comes to foods, K1 is especially abundant in green leafy vegetables.

K1 makes for 75–90% of the vitamin K in the Western diet.[15] Unfortunately, K1 is tightly bound to chloroplasts (organelles that contain chlorophyll and conduct photosynthesis), so you could be absorbing very little of what you eat[50] — maybe less than 10%.[51] Since vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin, however, its absorption can be enhanced by the co-ingestion of fat: adding fat to cooked spinach can raise K1 bioavailability from 5% to 13%.[52]

Vitamin K2

Things become more complicated here, because just as there are several forms of vitamin K, there are several forms of vitamin K2. To be more precise, the side chain of K1 always has four isoprenoid units (five-carbon structures), so there is only one form of K1, but the side chain of K2 has n isoprenoid units, so there are n forms of K2, called MK-n.[53][54]

Whereas the side chain of K1 has four saturated isoprenoid units, the side chain of K2 MK-4 has four unsaturated isoprenoid units. Although K1 is directly active in your system, your body can also convert it to MK-4.[11][55][56] How much gets converted depends notably on your genetic heritage.[15]

MK-4 is present in animal products (meat, eggs, and dairy), though only in small quantities. Because those foods usually contain fat, dietary MK-4 should be better absorbed than dietary K1,[57] but future studies will need to confirm this hypothesis.

Other than MK-4, all forms of K2 are produced by bacteria. Your microbiota was once thought to produce three-fourths of the vitamin K you absorb.[58] Vitamin K, however, is mostly produced in the colon, where there are no bile salts to facilitate its absorption, so the actual ratio is probably much lower.[57][59]

Bacteria-produced K2 can be found in fermented foods, such as cheese and curds, but also in liver meat.[60] The richest dietary source of K2 is natto (fermented soybeans), which contains mostly MK-7.[61][62] As it stands, MK-7 is the only form of K2 that can be consumed in supplemental doses through food (i.e., natto). For that reason, MK-7 is the most-studied form of K2, together with MK-4.

K1 and MK-4 both have a side chain composed of four isoprenoid units; their half-life in your blood is 60–90 minutes. MK-7 has a side chain composed of seven isoprenoid units; it remains in your blood for several days. Due to their different side-chain lengths, the various forms tend to be transported on different lipoproteins, which are taken up at different rates by various tissues.[63][64][65][66][67] K1 and MK-4 are used quickly (K1 in the liver, MK-4 in other specific tissues), whereas MK-7 has more time to travel and be used throughout the body (which makes it, in theory, the best option for bone health).

Vitamin K3

K1 and K2 are the only natural forms of vitamin K, but there exist several synthetic forms, the best known of which is K3. However, whereas the natural forms of vitamin K are safe, even in high doses, K3 can interfere with glutathione, your body’s main antioxidant. K3 was once used to treat vitamin K deficiency in infants, but it caused liver toxicity, jaundice, and hemolytic anemia. Nowadays, it is used only in animal feed, in small doses. In the animals, vitamin K3 gets converted into K2 MK-4,[68] which you can consume safely.

Vitamin K is a family of fat-soluble vitamins. K1 and K2, the natural forms, are safe even in high doses. There is only one type of K1; it is found in plants, notably green leafy vegetables; your body can use it directly or convert it to K2 MK-4. Aside from MK-4, all other types of K2 are produced by bacteria, including the bacteria populating your gut. MK-4 is present in animal products (meat, eggs, dairy), whereas other types of K2 can be found in fermented foods and liver meat.

Vitamin K and your health

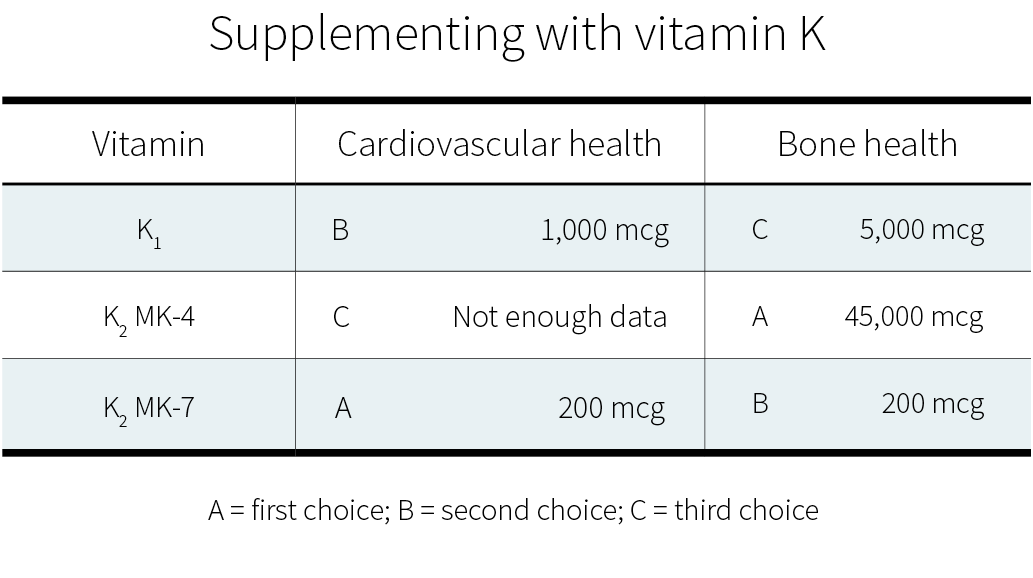

As far as we know, vitamin K mainly affects bloodclotting, cardiovascular health, and bone health. Epidemiological studies have mostly focused on K1; cardiovascular trials, on K1 and MK-7 (the main type present in natto, the richest dietary source of K2); bone trials, on MK-4 (the type of K2 your body can make out of K1).

Blood clotting

Vitamin K deficiency impairs blood clotting, causing excessive bleeding and bruising. It is rare in adults, but more common in newborns (more than 4 cases per 100,000 births in the UK[69]), where it can result in life-threatening bleeding within the skull. For that reason, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that newborns receive K1 shortly after birth (intramuscular injections have shown greater efficacy than oral administration).[70]

If you suffer from hypercoagulation (if your blood clots too easily), you might be prescribed a vitamin K antagonist (VKA), such as warfarin, a medication that hinders the recycling of vitamin K. Some doctors recommend that VKA users shun vitamin K entirely, but preliminary evidence suggests that, under professional supervision, vitamin K supplements might help stabilize the effects of VKAs.[60]

Which form should be supplemented, though, and in what amount, is still uncertain. There is some evidence that K1 enhances coagulation more than does MK-4[71][72] but less than does MK-7.[65] With regard to daily supplementation, 100 μg of K1 is considered safe, but in some people 10 μg of MK-7 is enough to significantly impair VKA therapy.[73]

Remember that natto is rich in MK-7. A single serving of natto can increase blood clotting for up to four days,[74] so it is one food VKA users should avoid. Other foods should be safe to eat. Please note that in people who do not suffer from hypercoagulation, and thus do not need to medicate with VKA, high intakes of natto have never been correlated to excessive blood clotting. Similarly, human studies saw no increase in blood-clot risk even from 45 mg (45,000 μg) of MK-4 taken once[75] or even thrice[76] daily.

Cardiovascular health

As we saw, vitamin K partakes in calcium regulation: it helps ensure that more calcium gets deposited in bones and less in soft tissues, thus reducing arterial stiffness. This is why people who take vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, are more likely to suffer from vascular calcification.[77][78]

Epidemiological studies[79][80][81] and mechanistic evidence[82] suggest that dietary K2 benefits cardiovascular health more than an equal dose of dietary K1.

Clinical trials on supplemental vitamin K have focused on K1[83][84] and MK-7.[85][86][87] Often, those trials used a combination of vitamin D and other nutrients, but with vitamin K being the key difference between the intervention group and the control groups. Both of these forms of vitamin K seem to cause a consistent reduction in arterial stiffness (with better evidence for MK-7), and less consistent reductions in coronary calcification and carotid intima-media thickness. Judging from those trials and the epidemiological evidence, MK-7 seems the better choice.

Bone health

As we have just seen again, vitamin K partakes in calcium regulation: it helps ensure that less calcium gets deposited in soft tissues and more in bones, thus strengthening the latter. This is why people who take vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, might be more at risk of bone fractures,[88][89] though not all studies agree they are.[90]

Current evidence suggests that supplementing with vitamin K — or, at least, with certain forms of vitamin K — can benefit bone health, especially in the elderly (who have lower levels of circulating K2).[91] This potential should be explored, since, as the world population grows (and grows older), so does the number of osteoporotic fractures.[92] [93][94]

MK-7 appears to support the carboxylation of osteocalcin (a major calcium-binding protein in bones) more efficiently than K1.[65] Clinical trials suggest that, for the purpose of increasing bone density, MK-4 and MK-7 work more reliably than K1.[3]

More significantly, a meta-analysis of MK-4 trials found an overall decrease in fracture risk.[95] The effect of K1 or MK-7 supplementation on fracture risk is less clear. Only one K1 trial looked at fracture risk; it reported a decrease, but without a concomitant increase in bone mineral density.[96] Of the two MK-7 trials, one reported no difference in the number of fractures between the placebo group and the MK-7 group,[97] whereas the other reported fewer fractures in the MK-7 group;[98] there were, however, no statistical analyses for either study.

More research on vitamin K and fracture risk will be needed to clarify the effects of the different forms at different dosages. Currently, if you wish to supplement for bone health, a very high dose of MK-4 (45,000 μg) is the option best supported by human studies.[95] Those studies, all in Japanese people, focused on the prevention of bone fractures, and yes, much smaller dosages can probably help support bone health; but how much smaller?

In a 12-month study, 20 patients suffering from a chronic kidney disorder were given a daily glucocorticoid (a corticosteroid that has for side effect to decrease bone formation and increase bone resorption). In addition, half the patients received 15 mg of MK-4 daily, while the other half received a placebo. The placebo group experienced bone-density loss (BDL) in the lumbar spine, while the MK-4 group did not.[99]

More recently, a 12-month study in 48 postmenopausal Japanese women gave 1.5 mg of MK-4 daily to half of them and found a significant reduction in forearm BDL, but not in hip BDL, and it didn’t evaluate fractures.[100]

So there is some evidence for dosages lower than 45 mg/day. It is, however, a lot weaker.

In healthy people, vitamin K supplementation does not increase the risk of blood clots. Judging from limited evidence, MK-7 seems to be the best form of vitamin K for cardiovascular health, and MK-4 the best form of vitamin K for bone health.

How much vitamin K do you need?

Since vitamin K is crucial to your health, why is it the subject of relatively few studies? One of the reasons is simply that vitamin K deficiency is very rare in healthy, well-fed adults. It is mostly a concern in newborns, in people who have been prescribed a vitamin K antagonist, in people who suffer from severe liver damage, and in people who have problems absorbing fat.[101][102][103]

Vitamin K is abundant in a balanced diet, and the bacteria in your colon can also produce some. Moreover, your body can recycle it many times, and this vitamin K-epoxide cycle more than makes up for the limited ability your body shows for storing vitamin K.

Still, you can recycle vitamin K many times, but not forever, and so you still need to consume some regularly. But how much, exactly?

No one knows. There is, as yet, not enough evidence to set a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin K, so an Adequate Intake (AI) has been established at a level assumed to prevent excessive bleeding. In the United States, the AI for vitamin K is 120 μg/day for men and 90 μg/day for women. In Europe, the AI for vitamin K is 70 μg/day for men and women. More recent research, however, suggests that those numbers should be increased.[64]

Since 100 g of collards contain, on average, 360 μg of vitamin K,[104][53] getting enough vitamin K looks easy. But can’t you just as easily get too much?

Fortunately, no. Though allergic reactions have occurred with vitamin K injections,[105][106][107] no incidence of actual toxicity has ever been reported in people taking natural vitamin K, even in high supplemental doses.[1] For that reason, neither the FDA nor the EFSA has set a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin K. One should note, however, that we lack long-term, high-dose studies on vitamin K safety.

Sources of vitamin K

K1 can be found in plant products, notably green leafy vegetables. K2 MK-4 can be found in animal products (meat, eggs, and dairy). The other types of K2 can be found in fermented foods and liver meat.

Table references: [108][109][53][110][111][67][104][112][113]

Meats’ vitamin K content correlates positively but non-linearly with their fat content and will vary according to the animal’s diet (and thus country of origin). Forms of K2 other than MK-4 and MK-7 have not been well studied but are likely to have some benefit — cheeses and beef liver are notable sources of others forms of K2[109][113] and cheese consumption is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.[114]

While well-conducted controlled trials provide the most reliable evidence, most such trials used amounts of vitamin K2 that far exceed what could be obtained through foods, save for natto. This leaves us wondering if dietary K2 has any effect.

Fortunately, it seems to be the case: a high dietary intake of K2 (≥33 μg/day seems optimal) may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease — an effect a high dietary intake of K1 doesn’t appear to have.[79][81][80][115] It doesn’t mean, of course, that foods rich in K1 are valueless: dietary K1 intake will protect you from excessive bleeding and is inversely associated with risk of bone fractures.[116]

Observational studies, however, are less reliable than controlled trials, so we know less about the effects of dietary intake than about the effects of supplemental intake. If you wish to supplement with vitamin K, here are the dosages supported by the current evidence:

Summary

Although much more research needs to be performed, there is early evidence that vitamin K, whether in food or in supplemental form, can benefit cardiovascular health and bone health.

Update History

Table added

Research written by

Full page update

Research written by

Edited by

Reviewed by

References

- ^Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on MicronutrientsDietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc

- ^EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA), Turck D, Bresson JL, Burlingame B, Dean T, Fairweather-Tait S, Heinonen M, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Mangelsdorf I, McArdle HJ, Naska A, Nowicka G, Pentieva K, Sanz Y, Siani A, Sjödin A, Stern M, Tomé D, Van Loveren H, Vinceti M, Willatts P, Lamberg-Allardt C, Przyrembel H, Tetens I, Dumas C, Fabiani L, Ioannidou S, Neuhäuser-Berthold MDietary reference values for vitamin K.EFSA J.(2017 May)

- ^Fang Y, Hu C, Tao X, Wan Y, Tao FEffect of vitamin K on bone mineral density: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Bone Miner Metab.(2012 Jan)

- ^Mott A, Bradley T, Wright K, Cockayne ES, Shearer MJ, Adamson J, Lanham-New SA, Torgerson DJEffect of vitamin K on bone mineral density and fractures in adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.Osteoporos Int.(2019-Aug)

- ^Salma, Ahmad SS, Karim S, Ibrahim IM, Alkreathy HM, Alsieni M, Khan MAEffect of Vitamin K on Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk in Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.Biomedicines.(2022 May 1)

- ^US Department of AgricultureFoods containing Phylloquinone (FoodData Central); Country: USA, cited 2024-05-13

- ^US Department of AgricultureFoods containing Dihydrophylloquinone (FoodData Central); Country: USA, cited 2024-05-13

- ^US Department of AgricultureFoods containing Menaquinone-4 (FoodData Central); Country: USA, cited 2024-05-13

- ^Dietary Supplement Fact Sheets; USA: National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS)(2022-06)

- ^Mladěnka P, Macáková K, Kujovská Krčmová L, Javorská L, Mrštná K, Carazo A, Protti M, Remião F, Nováková L, OEMONOM researchers and collaboratorsVitamin K - sources, physiological role, kinetics, deficiency, detection, therapeutic use, and toxicity.Nutr Rev.(2022 Mar 10)

- ^Shearer MJ, Newman PMetabolism and cell biology of vitamin KThromb Haemost.(2008 Oct)

- ^Shearer MJ, Okano TKey Pathways and Regulators of Vitamin K Function and Intermediary Metabolism.Annu Rev Nutr.(2018 Aug 21)

- ^US Department of AgricultureNatto (FoodData Central); Country: USA, cited 2024-05-27

- ^European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)Vitamin K2 added for nutritional purposes in foods for particular nutritional uses, food supplements and foods intended for the general population and Vitamin K2 as a source of vitamin K added for nutritional purposes to foodstuffs, in the context of Regulation (EC) N° 258/97EFSA J.(2008-11-14)

- ^Shearer MJ, Newman PRecent trends in the metabolism and cell biology of vitamin K with special reference to vitamin K cycling and MK-4 biosynthesisJ Lipid Res.(2014 Mar)

- ^European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)Scientific Opinion on the safety and efficacy of vitamin K3 (menadione sodium bisulphite and menadione nicotinamide bisulphite) as a feed additive for all animal speciesEFSA J.(2014-01-16)

- ^Hurley DL, Binkley N, Camacho PM, Diab DL, Kennel KA, Malabanan A, Tangpricha VTHE USE OF VITAMINS AND MINERALS IN SKELETAL HEALTH: AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY POSITION STATEMENT.Endocr Pract.(2018 Oct 2)

- ^Ng E, Loewy ADPosition Statement: Guidelines for vitamin K prophylaxis in newborns: A joint statement of the Canadian Paediatric Society and the College of Family Physicians of Canada.Can Fam Physician.(2018 Oct)

- ^Mihatsch WA, Braegger C, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellöf M, Fewtrell M, Mis NF, Hojsak I, Hulst J, Indrio F, Lapillonne A, Mlgaard C, Embleton N, van Goudoever J, ESPGHAN Committee on NutritionPrevention of Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding in Newborn Infants: A Position Paper by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.(2016 Jul)

- ^Ardell S, Offringa M, Ovelman C, Soll RProphylactic vitamin K for the prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding in preterm neonates.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.(2018 Feb 5)

- ^European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to vitamin K and maintenance of bone (ID 123, 127, 128, and 2879), blood coagulation (ID 124 and 126), and function of the heart and blood vessels (ID 124, 125 and 2880) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006EFSA J.(2009-10-01)

- ^Booth SL, Broe KE, Gagnon DR, Tucker KL, Hannan MT, McLean RR, Dawson-Hughes B, Wilson PW, Cupples LA, Kiel DPVitamin K intake and bone mineral density in women and men.Am J Clin Nutr.(2003 Feb)

- ^Kanai T, Takagi T, Masuhiro K, Nakamura M, Iwata M, Saji FSerum vitamin K level and bone mineral density in post-menopausal women.Int J Gynaecol Obstet.(1997 Jan)

- ^Chin KYThe Relationship between Vitamin K and Osteoarthritis: A Review of Current Evidence.Nutrients.(2020 Apr 25)

- ^Shea MK, Booth SL, Miller ME, Burke GL, Chen H, Cushman M, Tracy RP, Kritchevsky SBAssociation between circulating vitamin K1 and coronary calcium progression in community-dwelling adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.Am J Clin Nutr.(2013 Jul)

- ^Chen HG, Sheng LT, Zhang YB, Cao AL, Lai YW, Kunutsor SK, Jiang L, Pan AAssociation of vitamin K with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Eur J Nutr.(2019-Sep)

- ^Zhang S, Guo L, Bu CVitamin K status and cardiovascular events or mortality: A meta-analysis.Eur J Prev Cardiol.(2019 Mar)

- ^Hartley L, Clar C, Ghannam O, Flowers N, Stranges S, Rees KVitamin K for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev.(2015 Sep 21)

- ^Zhao QY, Li Q, Hasan Rashedi M, Sohouli M, Rohani P, Velu PThe effect of vitamin K supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis.J Nutr Sci.(2024)

- ^Caitlyn Vlasschaert, Chloe J Goss, Nathan G Pilkey, Sandra McKeown, Rachel M HoldenVitamin K Supplementation for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Where Is the Evidence? A Systematic Review of Controlled TrialsNutrients.(2020 Sep 23)

- ^Geng C, Huang L, Pu L, Feng YEffects of vitamin K supplementation on vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.Front Nutr.(2022)

- ^Qu B, Yan S, Ao Y, Chen X, Zheng X, Cui WThe relationship between vitamin K and T2DM: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Food Funct.(2023 Oct 2)

- ^Shahdadian F, Mohammadi H, Rouhani MHEffect of Vitamin K Supplementation on Glycemic Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials.Horm Metab Res.(2018 Mar)

- ^Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Darli Ko Ko HEffect of vitamin K supplementation on insulin sensitivity: a meta-analysis.Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes.(2017)

- ^Dariimaa Ganbat, Bat-Erdene Jugder, Lkhamaa Ganbat, Miki Tomoeda, Erdenetsogt Dungubat, Yoshihisa Takahashi, Ichiro Mori, Takayuki Shiomi, Yasuhiko TomitaThe Efficacy of Vitamin K, A Member Of Naphthoquinones in the Treatment of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisCurr Cancer Drug Targets.(2021)

- ^Koklu E, Taskale T, Koklu S, Ariguloglu EAAnaphylactic shock due to vitamin K in a newborn and review of literature.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.(2014 Jul)

- ^Zhang M, Chen J, Wang CX, Lin NX, Li XCutaneous allergic reaction to subcutaneous vitamin K(1): A case report and review of literature.World J Clin Cases.(2022 Oct 16)

- ^Marles RJ, Roe AL, Oketch-Rabah HAUS Pharmacopeial Convention safety evaluation of menaquinone-7, a form of vitamin K.Nutr Rev.(2017 Jul 1)

- ^European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)Vitamin K2 added for nutritional purposes in foods for particular nutritional uses, food supplements and foods intended for the general population and Vitamin K2 as a source of vitamin K added for nutritional purposes to foodstuffs, in the context of Regulation (EC) N° 258/97EFSA J.(2008-11-14)

- ^Dowd P, Ham SW, Naganathan S, Hershline RThe mechanism of action of vitamin K.Annu Rev Nutr.(1995)

- ^Villa JKD, Diaz MAN, Pizziolo VR, Martino HSDEffect of vitamin K in bone metabolism and vascular calcification: A review of mechanisms of action and evidences.Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.(2017 Dec 12)

- ^Vermeer C, Jie KS, Knapen MHRole of vitamin K in bone metabolism.Annu Rev Nutr.(1995)

- ^Alonso N, Meinitzer A, Fritz-Petrin E, Enko D, Herrmann MRole of Vitamin K in Bone and Muscle Metabolism.Calcif Tissue Int.(2023 Feb)

- ^Eden RE, Daley SF, Coviello JMVitamin K Deficiency.StatPearls.(2024 Jan)

- ^Card DJ, Gorska R, Harrington DJLaboratory assessment of vitamin K status.J Clin Pathol.(2020 Feb)

- ^Nijsten K, van der Minnen L, Wiegers HMG, Koot MH, Middeldorp S, Roseboom TJ, Grooten IJ, Painter RCHyperemesis gravidarum and vitamin K deficiency: a systematic review.Br J Nutr.(2022 Jul 14)

- ^Marlena S Fejzo, Jone Trovik, Iris J Grooten, Kannan Sridharan, Tessa J Roseboom, Åse Vikanes, Rebecca C Painter, Patrick M MullinNausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarumNat Rev Dis Primers.(2019 Sep 12)

- ^Dam HThe antihaemorrhagic vitamin of the chickBiochem J.(1935 Jun)

- ^Booth SLRoles for vitamin K beyond coagulationAnnu Rev Nutr.(2009)

- ^Garber AK, Binkley NC, Krueger DC, Suttie JWComparison of phylloquinone bioavailability from food sources or a supplement in human subjectsJ Nutr.(1999 Jun)

- ^Gijsbers BL, Jie KS, Vermeer CEffect of food composition on vitamin K absorption in human volunteersBr J Nutr.(1996 Aug)

- ^Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, Crowther M, Hylek EM, Palareti GOral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest.(2012 Feb)

- ^Booth SLVitamin K: food composition and dietary intakesFood Nutr Res.(2012)

- ^Kurosu M, Begari EVitamin K2 in electron transport system: are enzymes involved in vitamin K2 biosynthesis promising drug targets?Molecules.(2010 Mar 10)

- ^Davidson RT, Foley AL, Engelke JA, Suttie JWConversion of dietary phylloquinone to tissue menaquinone-4 in rats is not dependent on gut bacteriaJ Nutr.(1998 Feb)

- ^Ronden JE, Drittij-Reijnders MJ, Vermeer C, Thijssen HHIntestinal flora is not an intermediate in the phylloquinone-menaquinone-4 conversion in the ratBiochim Biophys Acta.(1998 Jan 8)

- ^Beulens JW, Booth SL, van den Heuvel EG, Stoecklin E, Baka A, Vermeer CThe role of menaquinones (vitamin K₂) in human healthBr J Nutr.(2013 Oct)

- ^Miggiano GA, Robilotta LVitamin K-controlled diet: problems and prospectsClin Ter.(2005 Jan-Apr)

- ^Ichihashi T, Takagishi Y, Uchida K, Yamada HColonic absorption of menaquinone-4 and menaquinone-9 in ratsJ Nutr.(1992 Mar)

- ^Holmes MV, Hunt BJ, Shearer MJThe role of dietary vitamin K in the management of oral vitamin K antagonistsBlood Rev.(2012 Jan)

- ^Ikeda Y, Iki M, Morita A, Kajita E, Kagamimori S, Kagawa Y, Yoneshima HIntake of fermented soybeans, natto, is associated with reduced bone loss in postmenopausal women: Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) StudyJ Nutr.(2006 May)

- ^Katsuyama H, Ideguchi S, Fukunaga M, Saijoh K, Sunami SUsual dietary intake of fermented soybeans (Natto) is associated with bone mineral density in premenopausal womenJ Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo).(2002 Jun)

- ^Sato T, Schurgers LJ, Uenishi KComparison of menaquinone-4 and menaquinone-7 bioavailability in healthy womenNutr J.(2012 Nov 12)

- ^Vermeer CVitamin K: the effect on health beyond coagulation - an overviewFood Nutr Res.(2012)

- ^Schurgers LJ, Teunissen KJ, Hamulyák K, Knapen MH, Vik H, Vermeer CVitamin K-containing dietary supplements: comparison of synthetic vitamin K1 and natto-derived menaquinone-7Blood.(2007 Apr 15)

- ^Schurgers LJ, Vermeer CDifferential lipoprotein transport pathways of K-vitamins in healthy subjectsBiochim Biophys Acta.(2002 Feb 15)

- ^Schurgers LJ, Vermeer CDetermination of phylloquinone and menaquinones in food. Effect of food matrix on circulating vitamin K concentrationsHaemostasis.(2000 Nov-Dec)

- ^Nakagawa K, Hirota Y, Sawada N, Yuge N, Watanabe M, Uchino Y, Okuda N, Shimomura Y, Suhara Y, Okano TIdentification of UBIAD1 as a novel human menaquinone-4 biosynthetic enzymeNature.(2010 Nov 4)

- ^Shearer MJVitamin KLancet.(1995 Jan 28)

- ^American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and NewbornControversies concerning vitamin K and the newborn. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and NewbornPediatrics.(2003 Jul)

- ^Spronk HM, Soute BA, Schurgers LJ, Thijssen HH, De Mey JG, Vermeer CTissue-specific utilization of menaquinone-4 results in the prevention of arterial calcification in warfarin-treated ratsJ Vasc Res.(2003 Nov-Dec)

- ^Groenen-van Dooren MM, Soute BA, Jie KS, Thijssen HH, Vermeer CThe relative effects of phylloquinone and menaquinone-4 on the blood coagulation factor synthesis in vitamin K-deficient ratsBiochem Pharmacol.(1993 Aug 3)

- ^Theuwissen E, Teunissen KJ, Spronk HM, Hamulyák K, Ten Cate H, Shearer MJ, Vermeer C, Schurgers LJEffect of low-dose supplements of menaquinone-7 (vitamin K2 ) on the stability of oral anticoagulant treatment: dose-response relationship in healthy volunteersJ Thromb Haemost.(2013 Jun)

- ^Schurgers LJ, Shearer MJ, Hamulyák K, Stöcklin E, Vermeer CEffect of vitamin K intake on the stability of oral anticoagulant treatment: dose-response relationships in healthy subjectsBlood.(2004 Nov 1)

- ^Ushiroyama T, Ikeda A, Ueki MEffect of continuous combined therapy with vitamin K(2) and vitamin D(3) on bone mineral density and coagulofibrinolysis function in postmenopausal womenMaturitas.(2002 Mar 25)

- ^Asakura H, Myou S, Ontachi Y, Mizutani T, Kato M, Saito M, Morishita E, Yamazaki M, Nakao SVitamin K administration to elderly patients with osteoporosis induces no hemostatic activation, even in those with suspected vitamin K deficiencyOsteoporos Int.(2001 Dec)

- ^Mayer O Jr, Seidlerová J, Bruthans J, Filipovský J, Timoracká K, Vaněk J, Cerná L, Wohlfahrt P, Cífková R, Theuwissen E, Vermeer CDesphospho-uncarboxylated matrix Gla-protein is associated with mortality risk in patients with chronic stable vascular diseaseAtherosclerosis.(2014 Jul)

- ^Chatrou ML, Winckers K, Hackeng TM, Reutelingsperger CP, Schurgers LJVascular calcification: the price to pay for anticoagulation therapy with vitamin K-antagonistsBlood Rev.(2012 Jul)

- ^Gast GC, de Roos NM, Sluijs I, Bots ML, Beulens JW, Geleijnse JM, Witteman JC, Grobbee DE, Peeters PH, van der Schouw YTA high menaquinone intake reduces the incidence of coronary heart diseaseNutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis.(2009 Sep)

- ^Beulens JW, Bots ML, Atsma F, Bartelink ML, Prokop M, Geleijnse JM, Witteman JC, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YTHigh dietary menaquinone intake is associated with reduced coronary calcificationAtherosclerosis.(2009 Apr)

- ^Geleijnse JM, Vermeer C, Grobbee DE, Schurgers LJ, Knapen MH, van der Meer IM, Hofman A, Witteman JCDietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease: the Rotterdam StudyJ Nutr.(2004 Nov)

- ^El Asmar MS, Naoum JJ, Arbid EJVitamin k dependent proteins and the role of vitamin k2 in the modulation of vascular calcification: a reviewOman Med J.(2014 May)

- ^Shea MK, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Dallal GE, Dawson-Hughes B, Ordovas JM, Price PA, Williamson MK, Booth SLVitamin K supplementation and progression of coronary artery calcium in older men and womenAm J Clin Nutr.(2009 Jun)

- ^Braam LA, Hoeks AP, Brouns F, Hamulyák K, Gerichhausen MJ, Vermeer CBeneficial effects of vitamins D and K on the elastic properties of the vessel wall in postmenopausal women: a follow-up studyThromb Haemost.(2004 Feb)

- ^Kurnatowska I, Grzelak P, Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Kaczmarska M, Stefańczyk L, Vermeer C, Maresz K, Nowicki MEffect of vitamin K2 on progression of atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in nondialyzed patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5Pol Arch Med Wewn.(2015)

- ^Knapen MH, Braam LA, Drummen NE, Bekers O, Hoeks AP, Vermeer CMenaquinone-7 supplementation improves arterial stiffness in healthy postmenopausal women. A double-blind randomised clinical trialThromb Haemost.(2015 May)

- ^Fulton RL, McMurdo ME, Hill A, Abboud RJ, Arnold GP, Struthers AD, Khan F, Vermeer C, Knapen MH, Drummen NE, Witham MDEffect of Vitamin K on Vascular Health and Physical Function in Older People with Vascular Disease--A Randomised Controlled TrialJ Nutr Health Aging.(2016 Mar)

- ^Caraballo PJ, Heit JA, Atkinson EJ, Silverstein MD, O'Fallon WM, Castro MR, Melton LJ 3rdLong-term use of oral anticoagulants and the risk of fractureArch Intern Med.(1999 Aug 9-23)

- ^Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Binder EFRisk of osteoporotic fracture in elderly patients taking warfarin: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation 2Arch Intern Med.(2006 Jan 23)

- ^Jamal SA, Browner WS, Bauer DC, Cummings SRWarfarin use and risk for osteoporosis in elderly women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research GroupAnn Intern Med.(1998 May 15)

- ^Hodges SJ, Pilkington MJ, Shearer MJ, Bitensky L, Chayen JAge-related changes in the circulating levels of congeners of vitamin K2, menaquinone-7 and menaquinone-8Clin Sci (Lond).(1990 Jan)

- ^Pisani P, Renna MD, Conversano F, Casciaro E, Di Paola M, Quarta E, Muratore M, Casciaro SMajor osteoporotic fragility fractures: Risk factor updates and societal impactWorld J Orthop.(2016 Mar 18)

- ^Dhanwal DK, Dennison EM, Harvey NC, Cooper CEpidemiology of hip fracture: Worldwide geographic variationIndian J Orthop.(2011 Jan)

- ^Johnell O, Kanis JAAn estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fracturesOsteoporos Int.(2006 Dec)

- ^Cockayne S, Adamson J, Lanham-New S, Shearer MJ, Gilbody S, Torgerson DJVitamin K and the prevention of fractures: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsArch Intern Med.(2006 Jun 26)

- ^Cheung AM, Tile L, Lee Y, Tomlinson G, Hawker G, Scher J, Hu H, Vieth R, Thompson L, Jamal S, Josse RVitamin K supplementation in postmenopausal women with osteopenia (ECKO trial): a randomized controlled trialPLoS Med.(2008 Oct 14)

- ^Emaus N, Gjesdal CG, Almås B, Christensen M, Grimsgaard AS, Berntsen GK, Salomonsen L, Fønnebø VVitamin K2 supplementation does not influence bone loss in early menopausal women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trialOsteoporos Int.(2010 Oct)

- ^Knapen MH, Drummen NE, Smit E, Vermeer C, Theuwissen EThree-year low-dose menaquinone-7 supplementation helps decrease bone loss in healthy postmenopausal womenOsteoporos Int.(2013 Sep)

- ^Sasaki N, Kusano E, Takahashi H, Ando Y, Yano K, Tsuda E, Asano YVitamin K2 inhibits glucocorticoid-induced bone loss partly by preventing the reduction of osteoprotegerin (OPG)J Bone Miner Metab.(2005)

- ^Koitaya N, Sekiguchi M, Tousen Y, Nishide Y, Morita A, Yamauchi J, Gando Y, Miyachi M, Aoki M, Komatsu M, Watanabe F, Morishita K, Ishimi YLow-dose vitamin K2 (MK-4) supplementation for 12 months improves bone metabolism and prevents forearm bone loss in postmenopausal Japanese womenJ Bone Miner Metab.(2013 May 24)

- ^Nowak JK, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Landowski P, Szaflarska-Poplawska A, Klincewicz B, Adamczak D, Banasiewicz T, Plawski A, Walkowiak JPrevalence and correlates of vitamin K deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel diseaseSci Rep.(2014 Apr 24)

- ^Jagannath VA, Fedorowicz Z, Thaker V, Chang ABVitamin K supplementation for cystic fibrosisCochrane Database Syst Rev.(2013 Apr 30)

- ^Nakajima S, Iijima H, Egawa S, Shinzaki S, Kondo J, Inoue T, Hayashi Y, Ying J, Mukai A, Akasaka T, Nishida T, Kanto T, Tsujii M, Hayashi NAssociation of vitamin K deficiency with bone metabolism and clinical disease activity in inflammatory bowel diseaseNutrition.(2011 Oct)

- ^Booth SL, Pennington JA, Sadowski JAFood sources and dietary intakes of vitamin K-1 (phylloquinone) in the American diet: data from the FDA Total Diet StudyJ Am Diet Assoc.(1996 Feb)

- ^Shiratori T, Sato A, Fukuzawa M, Kondo N, Tanno SSevere Dextran-Induced Anaphylactic Shock during Induction of Hypertension-Hypervolemia-Hemodilution Therapy following Subarachnoid HemorrhageCase Rep Crit Care.(2015)

- ^Riegert-Johnson DL, Volcheck GWThe incidence of anaphylaxis following intravenous phytonadione (vitamin K1): a 5-year retrospective reviewAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol.(2002 Oct)

- ^Bullen AW, Miller JP, Cunliffe WJ, Losowsky MSSkin reactions caused by vitamin K in patients with liver diseaseBr J Dermatol.(1978 May)

- ^Fu X, Shen X, Finnan EG, Haytowitz DB, Booth SLMeasurement of Multiple Vitamin K Forms in Processed and Fresh-Cut Pork Products in the U.S. Food SupplyJ Agric Food Chem.(2016 Jun 8)

- ^Manoury E, Jourdon K, Boyaval P, Fourcassié PQuantitative measurement of vitamin K2 (menaquinones) in various fermented dairy products using a reliable high-performance liquid chromatography methodJ Dairy Sci.(2013 Mar)

- ^Kamao M, Suhara Y, Tsugawa N, Uwano M, Yamaguchi N, Uenishi K, Ishida H, Sasaki S, Okano TVitamin K content of foods and dietary vitamin K intake in Japanese young womenJ Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo).(2007 Dec)

- ^Elder SJ, Haytowitz DB, Howe J, Peterson JW, Booth SLVitamin k contents of meat, dairy, and fast food in the u.s. DietJ Agric Food Chem.(2006 Jan 25)

- ^Shimogawara K, Muto SPurification of Chlamydomonas 28-kDa ubiquitinated protein and its identification as ubiquitinated histone H2BArch Biochem Biophys.(1992 Apr)

- ^Hirauchi K, Sakano T, Notsumoto S, Nagaoka T, Morimoto A, Fujimoto K, Masuda S, Suzuki YMeasurement of K vitamins in animal tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detectionJ Chromatogr.(1989 Dec 29)

- ^Chen GC, Wang Y, Tong X, Szeto IMY, Smit G, Li ZN, Qin LQCheese consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studiesEur J Nutr.(2017 Dec)

- ^Villines TC, Hatzigeorgiou C, Feuerstein IM, O'Malley PG, Taylor AJVitamin K1 intake and coronary calcificationCoron Artery Dis.(2005 May)

- ^Hao G, Zhang B, Gu M, Chen C, Zhang Q, Zhang G, Cao XVitamin K intake and the risk of fractures: A meta-analysisMedicine (Baltimore).(2017 Apr)